When you make a purchase through links on our article, Future and its syndicate partners may earn a commission.

A chemical mystery is unfolding in the laboratory of Tycho Brahe, one of the most famous astronomers of all time.

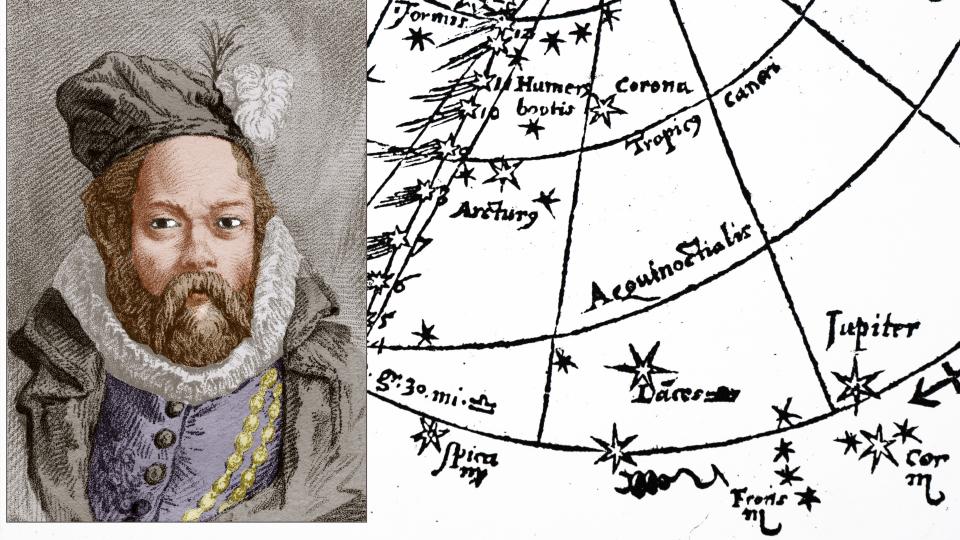

Tycho Brahe (1546-1603) was a leading enthusiast of Danish astronomy in the years before the telescope was used to look at the sky. Apart from that and the discovery of a great supernova, Brahe experimented with alchemy, which was a common practice during the Renaissance. Brahe tried to make alchemical remedies and other scientists tried, unsuccessfully as it turned out, to convert the basic elements into gold.

New analysis of pottery and glass shards excavated in Brahe’s laboratory between 1988 and 1990 revealed the popular alchemical ingredients gold and mercury. The study also found common elements of nickel, copper and zinc. The big surprise, however, was the discovery of tungsten; Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele first isolated the rare metal in 1781, nearly two centuries after Brahe’s death, according to the University of Southern Denmark.

Brahe’s approach to experimentation, whether in the laboratory or when he was looking at the sky, was pioneering in his day and was later adopted by eminent astronomers such as Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Alchemy and astronomy have been intrinsically linked for centuries, according to the UK Science Museum Group.

To be sure, the magical arts were also part of these scientists’ reasoning, but there was also a desire to “discover the hidden workings of nature,” assistant curator Katie Crowson wrote in the museum group post.

“This empiricist approach was embraced by those associated with the scientific revolution, a period of great change in scientific thinking in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that changed attitudes towards nature,” said Crowson.

Related: Famous astronomers: How these scientists shaped astronomy

It is not clear whether the tungsten was a deliberate act of Brahe’s chemistry. Clues to the existence of tungsten were known in Brahe’s time. There is little chance that Brahe knew: in the early 1500s, Georgius Agricola found a strange substance, which we now know to be tungsten, in tin ore from the German state of Saxony. (Back then, Saxony was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire, whose vast possessions included Brahe’s Denmark and Agricola’s seat in modern-day Germany.)

The substance, which Agricola and others called “Wolfram” (“Wolf’s froth” in German), caused difficulties when the mineralogist tried to extract the smell or tin from the ore.

“Maybe Tycho Brahe heard about this and therefore knew that tungsten was there,” said the study’s lead author, Kaare Lund Rasmussen, who is at the University of Denmark as an emeritus professor specializing in a branch of archeology known as archaeology.

Rasmussen emphasized that we cannot say for sure, however, whether Brahe intended to use tungsten. “This is not what we know or can say based on the analyzes I’ve done. It’s just a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples.”

Brahe’s medical alchemy addressed illness as a plague. Recipes were considered protected information at the time, and perhaps only a handful of people — such as his patron and financier, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II — received the recipes Brahe created.

The researchers suggested that Brahe’s “plague cure” or theriac (mixture of drugs) could have up to 60 ingredients, including substances such as opium, snake meat and copper, and various herbs and oils.

RELATED STORIES:

— The bones of Danish Astronomer Tycho Brahe may provide clues about his death

— Famous astronomers: How these scientists shaped astronomy

— Supernova Anniversary: The famous star Tycho exploded 450 years ago

Brahe created at least three recipes to combat plague; although tungsten was found in the laboratory, its presence (along with other elements not found in reconstructed recipes) is not proof that they were indeed used to make Brahe’s medicine,” the researchers warned in the study published July 25 in the journal. Heritage Science.

In addition to the value of the experiment, there is another link between astronomy and alchemy: Brahe expressed confidence in “links between the heavenly bodies, terrestrial substances, and the organs of the body,” study co-author Poul Grinder-Hansen, curator at the National. The Danish Museum, said in the same statement.

For example, Brahe said that “the sun, gold, and the heart are connected, and the same applies to the moon, money, and the brain.” This world view, since it was out of proportion, encouraged Brahe to experiment on himself; a previous study involving Rasmussen found gold and other elements in Brahe’s hair and bones.