Less than a month into the summer of 2024, the vast majority of the US population has already experienced an extreme heat wave. Millions of people were under heat warnings across the western US in early July or sweating through humid heat in the East.

Death Valley hit a dangerous 129 degrees Fahrenheit (53.9 C) on July 7, a day after a biker died from heat exposure there. Las Vegas broke his all-time heat record at 120 F (48.9 C). In California, days of heat over 100 degrees in large parts of the state parched the landscape, fueling wildfires. Oregon has reported several suspected heat deaths.

Extreme heat like this was hitting countries across the planet in 2024.

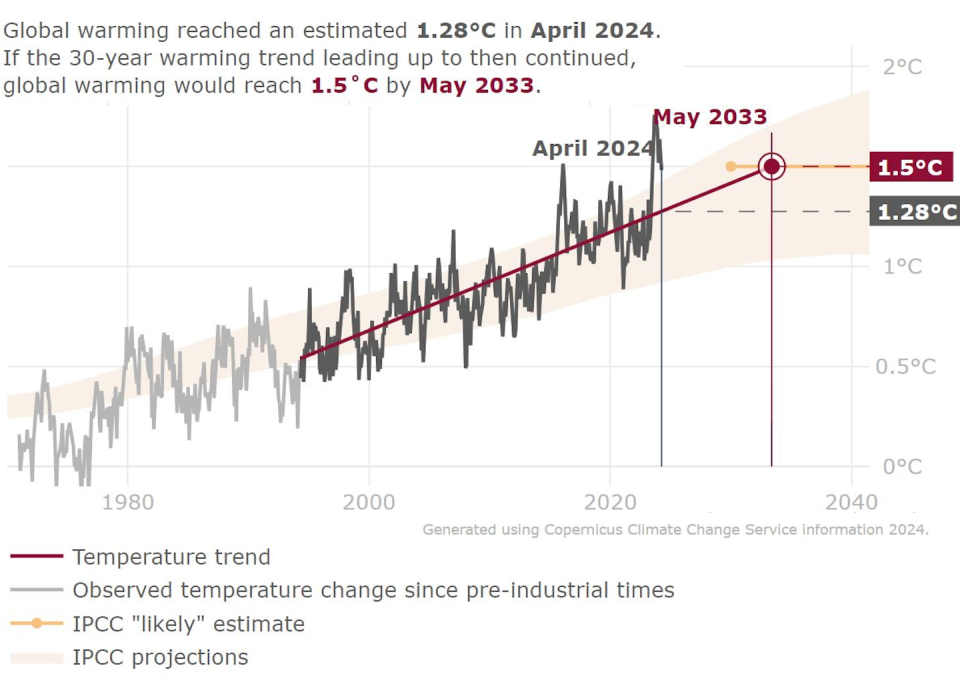

Globally, each of the past 13 months has been the warmest on record for that month, including the warmest June, according to the European Union’s Copernicus climate service. The service reported on July 8, 2024, that the average temperature for the previous 12 months was also at least 1.5 C (2.7 F) warmer than the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average.

The 1.5 C warming threshold can be confusing, so let’s take a closer look at what that means. In the Paris climate agreement, countries around the world agreed to work to keep global warming below 1.5 C, but that refers to the average temperature change over a period of 30 years. A 30-year average is used to limit the impact of natural fluctuations from year to year.

So far, Earth has only crossed that threshold for one year. It is a cause for concern, however, and the world appears to be on track to cross the 30-year average threshold of 1.5 C within 10 years.

We study weather patterns related to heat. The early season heat, part of a human-driven warming trend, is putting lives around the world at risk.

Heat is becoming a global problem

Record heat has hit several countries across the Americas, Africa, Europe and Asia in 2024. In Mexico and Central America, weeks of persistent heat that began in the spring of 2024 combined with a prolonged drought severe water shortages and many deaths.

Tragedy came from the extreme heat in Saudi Arabia, where more than 1,000 people collapsed and died on the Hajj, a Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca. The temperature reached 125 F (51.8 C) at the Grand Mosque in Mecca on June 17.

Hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan, were under siege amid weeks of high heat, frequent power outages, and water shortages in some areas. Temperatures hovered around 120 F (48.9 C) across neighboring India for several days in April and May, affecting millions of people, many without air conditioning.

In Greece, where temperatures topped 100 F (37.8 C) for days in June, several tourists died or were feared dead after hiking in dangerous heat and humidity.

Japan issued heat stroke warnings in Tokyo and more than half of its predecessors as temperatures rose to their highest level in early July.

The climate link: This is not ‘just summer’

Although heat waves are a natural part of the climate, the intensity and extent of heat waves so far in 2024 is not “just summer”.

A scientific assessment of the extreme heat wave in the eastern US in June 2024 estimates that such intense and prolonged heat was two to four times more likely today due to human-caused climate change than it would have been. without it. This conclusion is consistent with the rapid increase over the past few decades in the number of heat waves in the US and their occurrence outside of the summer peak.

The largest heat waves on record are occurring in a climate that is over 2.2 F (1.2 C) worldwide warmer – when looking at the 30-year average – than it was before the industrial revolution, when people started large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions were released that were warming. the climate.

Although a temperature difference of a degree or two may not be noticeable when you walk into another room, even fractions of a degree make a big difference in global climate.

At the peak of the last ice age, about 20,000 years ago, when the Northeastern US was under thousands of feet of ice, the average global temperature was only about 11 F (6 C) cooler than it is now. So it’s no surprise that 2.2 F (1.2 C) of warming so far is already rapidly changing the climate.

If you thought this was hot

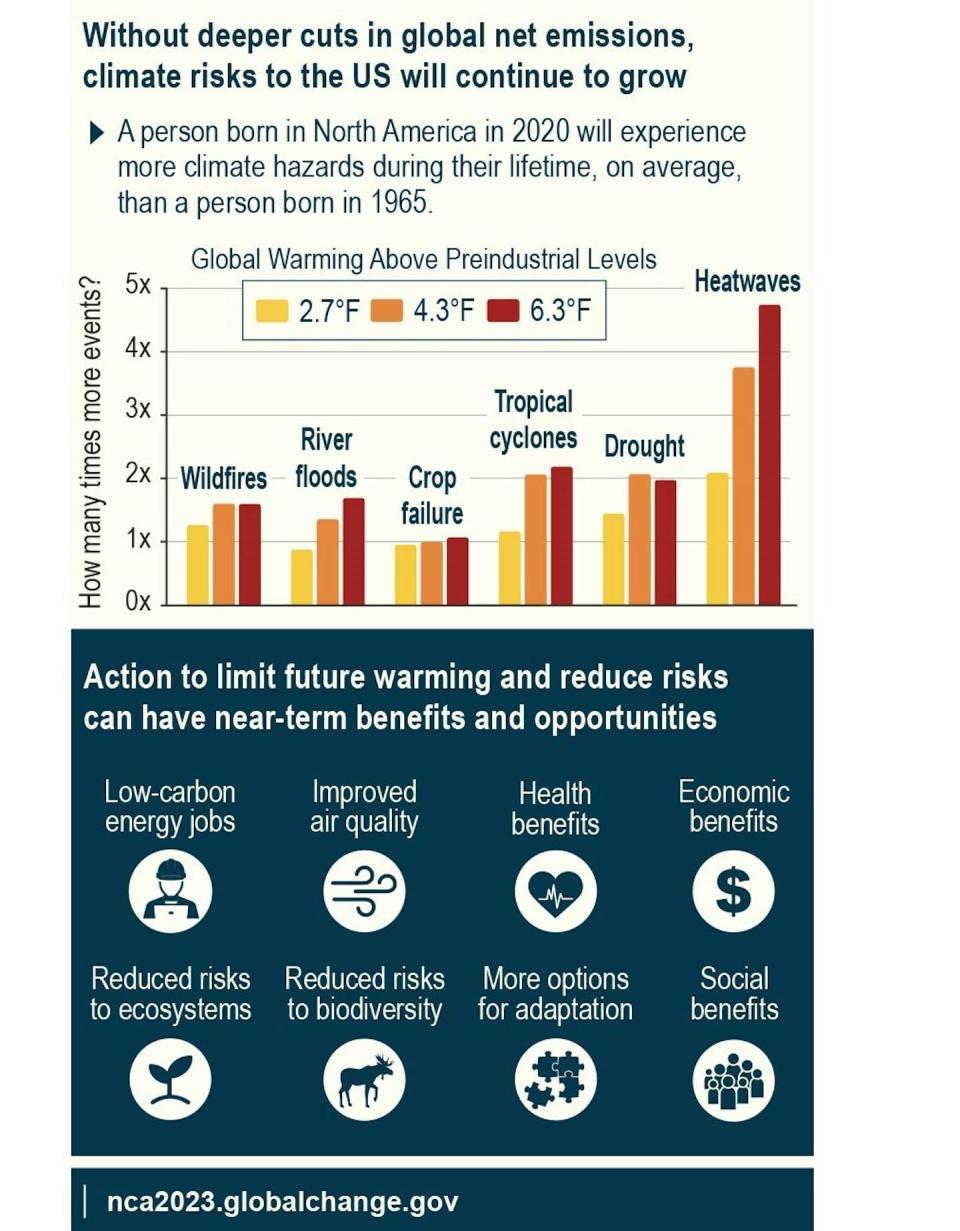

Although this summer is likely to be one of the hottest on record, it is important to realize that it could be one of the coldest summers to come.

For populations particularly vulnerable to heat, including young children, older adults and outdoor workers, the risks are even higher. People in lower-income neighborhoods where air conditioning may be unaffordable and renters who often don’t have the same protections for cooling and heating will face more dangerous conditions.

Extreme heat can also affect economies. It can buckle railroad tracks and cause wires to snap, causing transit delays and disruptions. It can also overload high-demand electrical systems and lead to blackouts right when people need cooling the most.

The good news: There are solutions

Yes, the future in a warming world is scary. However, while countries are not on track to meet their Paris Agreement targets, they have made progress.

In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 has the potential to cut US greenhouse gas emissions by nearly half by 2035.

Switching from air conditioners to heat pumps and geothermal network systems will not only reduce fossil fuel emissions but also provide lower cost cooling. The cost of renewable energy continues to fall, and many countries are increasing policy support and incentives.

There is much humanity can do to limit future warming if countries, companies and people everywhere act urgently. Rapidly reducing fossil fuel emissions can help avoid a warmer future and worse heat waves and droughts, while providing other benefits, including improved public health, jobs create and reduce risks to ecosystems.

This is an update to an article originally published on 26 June 2024.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Mathew Barlow, UMass Lowell and Jeffrey Basara, UMass Lowell

Read more:

Mathew Barlow has received funding from NOAA’s Modeling, Analysis, Projections and Projections Program to study heat waves.

Jeffrey Basara has received funding from the United States Department of Agriculture and the National Science Foundation to study flash drought and extreme temperatures.