Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

Researchers have discovered that the last meal of the tyrannosaur is perfectly preserved within its stomach cavity.

What was on the menu 75 million years ago? The last legs of two baby dinosaurs, according to new research on the fossil published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

Dinosaur intestines and hard evidence of their diets are rarely preserved in the fossil record, and this is the first time the contents of a tyrannosaur’s stomach have been discovered.

This revelation makes this discovery very exciting, said co-author Darla Zelenitsky, a paleontologist and associate professor at the University of Calgary in Alberta.

“Tyrannosaurs are these large prey species that roamed Alberta, and North America, during the late Cretaceous. These were the iconic or best predators we have all seen in movies, books and museums. They walked on two legs (and) had very short arms,” Zelenitsky said.

“It was a cousin of T. rex, which came later in time, 68 to 66 million years ago. T. rex is the largest tyrannosaurs, Gorgosaurus was a little smaller, maybe a total growth of 9, 10 meters (33 feet).

The tyrannosaur in question, a young Gorgosaurus libratus, would have weighed about 772 pounds (350 kilograms) – less than a horse – and was 13 feet (4 meters) long at the time of death.

The creature was between 5 and 7 years old and appeared to be picky about what it ate, Zelenitsky said.

“The last and second last meal were these little bird-like dinosaurs, Citipes, and the tyrannosaurus only ate the hind limbs of each of these prey items. There are actually no other skeletal remains of these predators within the stomach cavity. It’s just the last legs.

“He must have killed … both of the Citipes at different times and then ripped off the last legs and ate them and left the rest of the carcasses,” she said. “This teenager clearly had a passion for drumsticks.”

The two baby dinosaurs belonged to the species known as Citipes elegans and would have been less than 1 year old when the tyrannosaur hunted them, the researchers concluded.

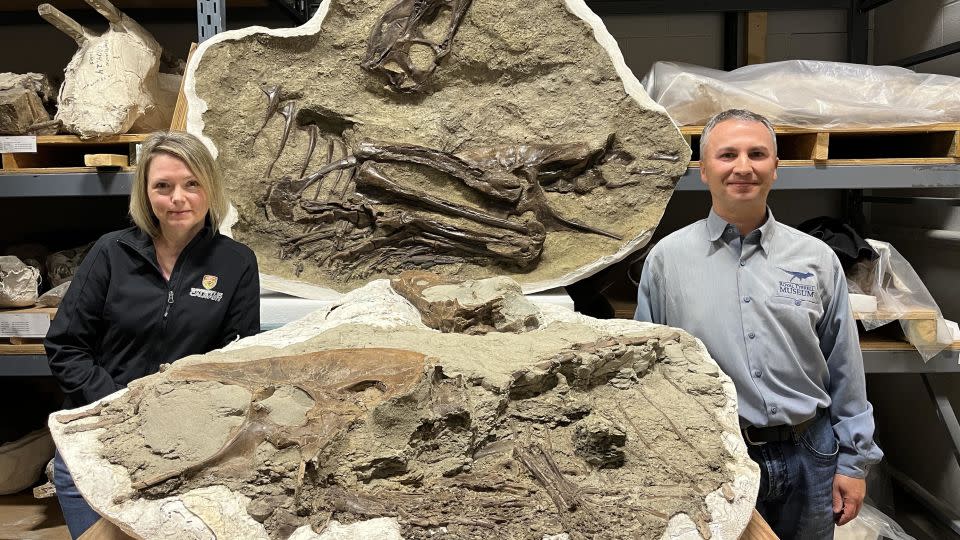

The nearly complete skeleton was found in Alberta Dinosaur Provincial Park in 2009.

It was not immediately clear that the tyrannosaur’s stomach contents had been preserved, but the team at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Eagle Ridge, Alberta, took small bones that had been pushing in while preparing the fossil in the laboratory and removed a rock inside its rib cage. to look at it more closely.

“Lo and behold, the complete hind legs of two baby dinosaurs, both under the age of one, were present in its stomach,” co-author François Therrien, the museum’s curator of dinosaur paleontology, said in a statement.

The paleontologists were able to determine the ages of both the predator and its prey by analyzing thin slices sampled from the fossilized bones.

“Growth marks are like tree rings. And we can basically tell how old a dinosaur is from looking at that, the bone structure,” Zelenitsky said.

Boiling changing top predators

The fossil is the first hard evidence of a diet pattern long suspected among large predatory dinosaurs, said paleoecologist Kat Schroeder, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at Yale University, who was not involved. with the research.

The teenage tyrannosaur didn’t eat what his parents did. Paleontologists believe that its diet would have changed over its lifetime.

“Big, strong tyrannosaurs like T. rex have strong enough bite forces to break through bone while they’re eating, so we know they gobble up mega-herbivores like Triceratops,” Schroeder said via the email. “Young tyrannosours can’t bite as deep, so don’t leave such feeding tracks.”

She said scientists had previously hypothesized that young tyrannosaurs had different diets from fully developed adults, but the fossil find is the first time researchers have direct evidence.

“Combined with the relative scarcity of juvenile tyrannosaur skeletons, this fossil is very significant,” Schroeder said. “Teeth can only tell us so much about the diet of extinct animals, so it’s like finding stomach contents and picking up the proverbial ‘smoking gun’.”

The contents of the tyrannosaur’s stomach cavity showed that juveniles at this stage of life hunted fast, small prey. Probably because the predator’s body was not yet well suited for larger prey, Zelenitsky said.

“It’s well known that tyrannosaurs changed a lot during growth, from slender forms to these strong, bone-crushing dinosaurs, and we know that this change was related to feeding behavior.”

When the dinosaur died, its mass was only 10% of the mass of an adult Gorgosaurus, she said.

How young tyrannosours filled a niche

The voracious appetite of the teenage tyrant and other carnivores is thought to explain the detrimental aspect of dinosaur diversity.

Small and medium-sized dinosaurs are few in the fossil record, especially in the Middle to Late Cretaceous Period – which paleontologists determined was due to the young tyrant’s hunting activities.

“In the Alberta Dinosaur Provincial Park, where this specimen came from, we have a very good sampling formation. And so we have a good idea of the ecosystem that exists. More than 50 species of dinosaurs,” Zelenitsky said.

“We’re missing medium-sized predators from that ecosystem. Yes, the hypothesis exists that the young tyrannosaurs filled that niche.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com