It will probably be a warmer world.

The increasing temperature of the Earth has clear consequences for human health, such as heat waves that are hotter than our physiology can tolerate. But humanity’s departure from the stable climate it inherited will surprise him too. Some of those diseases that will appear in new places or spread strongly may be existing diseases. And some, experts fear, may be completely new diseases.

This round of The Conversation climate coverage comes from our weekly climate action newsletter. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environmental editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who have subscribed.

The mosquito-borne infectious malaria has killed more than half a million people every year for the past decade. The majority of these victims were children and almost all of them (95% in 2022) were in Africa.

As a source of disease, infectious mosquitoes are at least predictable in their need for three things: warm temperatures, moist air and ponds to breed in. So what difference will global warming make?

Parasites are on the march

“The relationship between climate and malaria transmission is complex and has been the subject of intense study over the last few decades,” say water and health experts Mark Smith (University of Leeds) and Chris Thomas (University of Lincoln).

Read more: Mapping malaria in Africa: climate change study predicts where mosquitoes will breed in the future

Much of this research has focused on sub-Saharan Africa, the global epicenter of malaria cases and deaths. Smith and Thomas combined temperature and water movement projections to produce an analysis of malaria risk across the continent.

Their findings showed that conditions for malaria transmission will be less favorable overall, especially in west Africa. But where temperature and humidity are likely to be suitable for infectious mosquitoes in the future, it also happens to be where more people are expected to live, near rivers such as the Nile in Egypt.

“This means that by 2100 the number of people living in potentially endemic malaria areas (suitable for transmission more than nine months a year) will increase to over a billion,” they say.

Elsewhere, tropical diseases will slip their bonds as the insects carrying them live further from the equator. This is already happening in France, where cases of dengue fever increased during the hot summer of 2022.

“It seems that the lowlands of Veneto [in Italy] emerging as an ideal habitat for the Culex mosquitoes, which can host and transmit West Nile virus,” says Michael Head, senior research fellow in global health at the University of Southampton.

Read more: Dengue in France: tropical diseases may not be so rare in Europe for much longer

Research suggests global transmission of mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue will change, says Mark Booth, senior lecturer in parasite epidemiology at Newcastle University. That’s as clear a picture as Booth could paint from modeling more than 20 tropical diseases in a warming world.

“For most of the other patents, there was little or no evidence. We don’t know what to expect,” he says.

Read more: Why climate change is making parasitic diseases harder to predict

Certain diseases will bring fresh torment to the farm human species. Bluetongue, a midge-borne virus, is expected to infect sheep further afield – in central Africa, western Russia and the United States – than in subtropical Asia and Africa where it originated, which says Booth.

And the prognoses for some diseases that affect people will worsen. UCL academics Sanjay Sisodiya, a neuroscientist and Mark Maslin, an earth systems scientist, discovered that climate change is worsening the symptoms of certain brain conditions.

Read more: Climate change linked to worsening brain diseases – new study

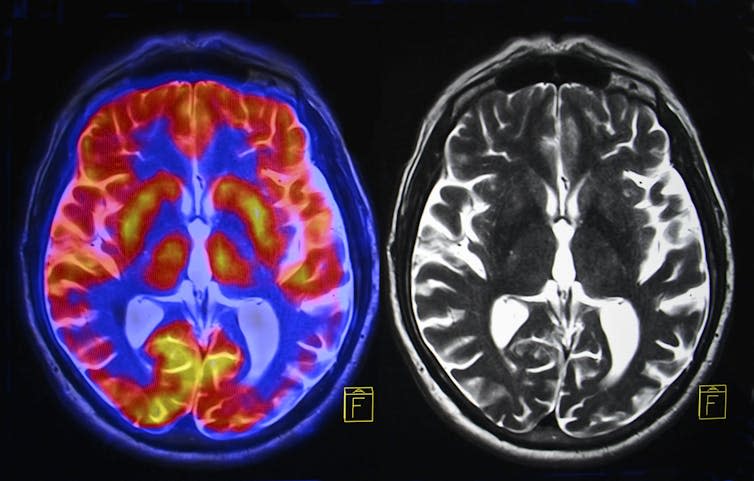

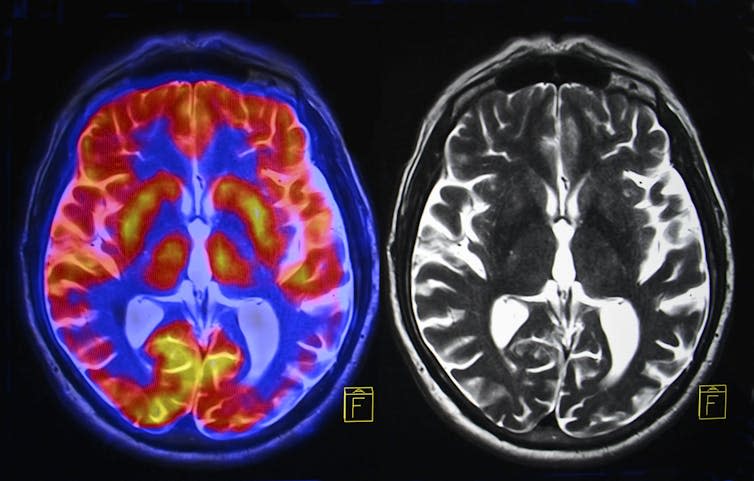

“Each of the billions of neurons in our brain is like a learning, adaptive computer with many electrically active components,” they say. “Many of these components operate at a different rate depending on the ambient temperature, and are designed to work together within a narrow temperature range.”

A species that evolved in Africa, humans are comfortable between 20˚C and 26˚C and within 20% and 80% humidity, say Sisodiya and Maslin. Our brain is already working close to the limit of its preferred temperature range in most cases, so even small increases matter.

“When those environmental conditions move rapidly into unusual ranges, as is happening with extreme temperatures and humidity associated with climate change, our brain struggles to regulate our temperature and begins to malfunction.”

One planet, one health

Clearly, staying healthy is not as simple as controlling what you eat or how often you exercise. There is a lot that you do not have immediate control over.

“Within less than three years, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared two public health emergencies of international concern: COVID-19 in February 2020 and monkeypox in July 2022,” says Arindam Basu, professor associate in epidemiology and environmental health at the University of Canterbury.

“At the same time, extreme events are continuously being reported around the world and are expected to become more frequent and more severe. These are not separate issues.”

Basu highlights the risk of new diseases emerging, particularly from pathogens that may jump between humans and animals as habitats change amid global warming.

Read more: One Health: why we need to combine disease surveillance and climate modeling to prevent future pandemics

“The close contact between humans and wild animals is increasing as forests are destroyed to make way for agriculture and trade in exotic animals continues,” he says. “At the same time, microbes hidden under the ice are being released by the melting of the permafrost.”

Since pathogens share the same ecosystems as the people and animals they infect, a new concept of health is urgently needed. This should aim to optimize the health of people, wildlife and the environment, says Basu.

Illness. Again, the climate crisis highlights our incalculable connection to everything else – and our partial weakness on the only planet known to harbor life.

This article from The Conversation is republished under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.