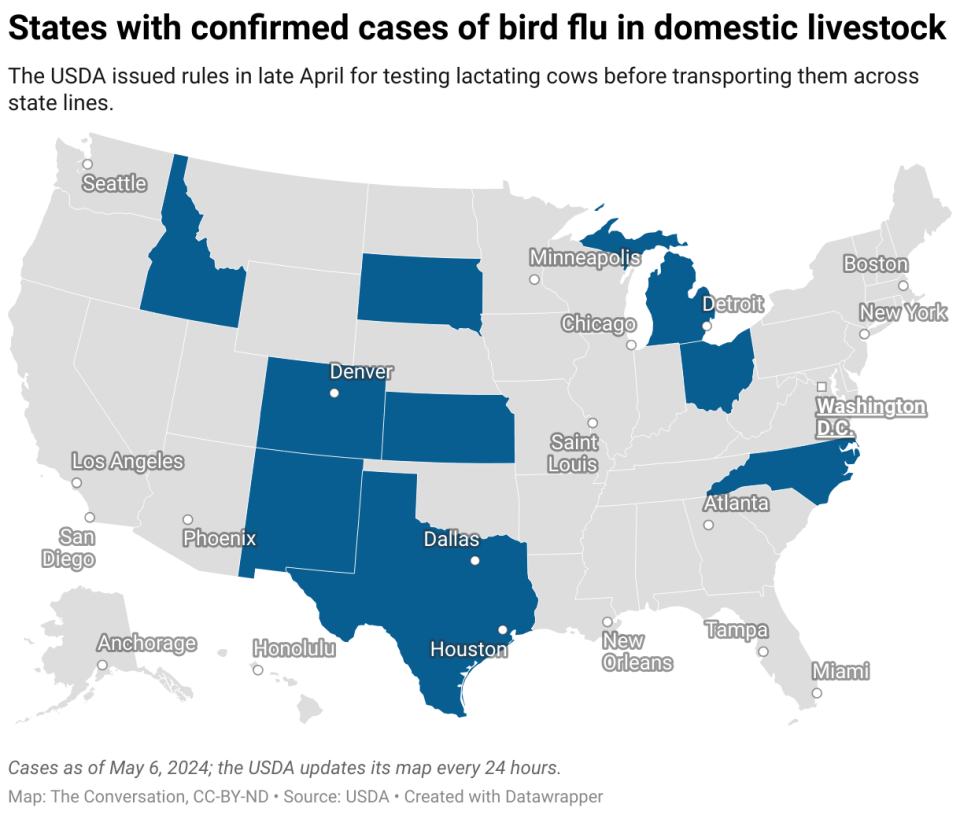

Colorado has highly pathogenic avian influenza – also known as HPAI or bird flu – on a dairy farm, the ninth state with confirmed cases. The US Department of Agriculture’s National Veterinary Services Laboratories confirmed the virus on April 25, 2024, in a herd in northeastern Colorado.

This farm is one of 35 dairy farms across the US with verified cases of bird flu in cattle as of May 7, 2024, according to the USDA.

Bird flu is nothing new in Colorado. The state had a poultry outbreak that began in 2022. Since then, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has reported that the virus has affected 6.3 million birds in nine commercial flocks and 25 backyard flocks. The most recent detection was in February 2024.

But this is the first time that the disease has made cattle in Colorado sick.

I am a veterinarian and epidemiologist at Colorado State University focusing on infectious diseases in dairy cows. I have spent many years on the USDA incident management team working on numerous cattle and poultry outbreaks, and I am leading Colorado State University’s efforts to study this latest outbreak.

The first cases of bird flu in cattle

Bird flu was first detected in dairy cattle in Texas and Kansas in March 2024.

Colorado State University faculty responded to the outbreak by forming a multistate group with state departments of agriculture, the USDA and other universities to better understand how this virus is transmitted between farms and among cows. The team is coordinating the sampling and testing of sick and healthy cows on affected farms to understand which animals are carrying the virus, which means they are most likely to spread the disease, and for how long.

We are also working to identify mitigation steps to help control this disease. Our network of animal health specialists are working with dairy producers and updating them with new data on a weekly basis.

Detection of bird flu in cattle

In February 2024, veterinarians and researchers began testing blood, urine, feces, milk and nasal swab samples of sick cows. The virus was most frequently detected in raw milk, suggesting that the disease may have been spread to other cows during the milking process.

More recent laboratory tests have detected the virus in the cows’ nasal secretions for a short time before the virus appears in their raw milk.

In late April, the US Food and Drug Administration and USDA began testing commercial milk samples. So far, the authorities have not detected any live virus in these samples.

That’s expected because the pasteurization process, which heats milk to 161 degrees Fahrenheit (72 degrees Celsius) for at least 15 seconds, kills the virus. Pasteurization times and temperatures used in the US are designed to kill bacterial pathogens, but they are working against this virus.

Raw milk, as its name suggests, is not pasteurized. The CDC has linked drinking raw milk to many foodborne illnesses, including E. coli and salmonella. Another cause for concern is the presence of the virus that causes bird flu, H5N1.

Dairy producers are required to divert abnormal milk and milk from sick cows from the food supply to protect consumers.

In addition to milk, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service has tested samples of commercial ground beef from states with sick cows. No virus has been found in beef since 1 May 2024.

Slowing down the spread of the disease

At this early stage of the outbreak in dairy cows, researchers do not know exactly how bird flu spreads in cattle, so containment recommendations may change as more is learned.

I have seen many infected cows and they look gloomy and depressed, similar to how people feel during a viral infection. Many infected cows have flu-like symptoms, such as fever.

Many dairy producers segregate sick cows in hospital pens, away from healthy ones, so that sick cows can be easily monitored and treated.

Since the virus was found in nasal secretions during early infection, the water tanks for the drinking water of the herds could be a source of infection. Farmers should continue to clean these tanks at least weekly – and even more often in hospital pens – as a best practice.

Infected cows can recover

The good news is that most cows get better. Like someone with the flu, they respond to anti-inflammatory drugs and oral fluids.

A small percentage of cows develop secondary bacterial infections and die or are humanely euthanized. Some cows recover from the infection but stop producing milk and are culled from the herd and usually slaughtered for beef.

As the virus is most often found in milk from sick cows, our team advises dairy producers to follow best milking practices on the dairy farm, including disinfecting the cow’s teats before and after milking, even cows healthy.

Only one case of human conjunctivitis due to bird flu was reported in a dairy farm worker from Texas in late March. The worker was probably exposed by direct contact with infected cow’s milk or by rubbing eyes with hands or gloves that had been in contact with contaminated milk. The CDC recommends that farm workers wear personal protective equipment, including eye protection, when in direct or close physical contact with raw milk.

How dairy producers can protect herds

Viruses can end up on farms through the movement of cattle, people, vehicles, equipment and wild birds.

The US dairy industry has a Safe Milk Supply Plan that addresses emerging dairy cattle diseases overseas such as bird flu. The plan calls for increased biosecurity practices on farms during disease outbreaks.

Biosecurity practices include restricting the movement of cattle on and off farms, allowing only essential personnel access to cattle, preventing vehicles and equipment from other farms from entering cattle areas, and cleaning and disinfecting vehicles entering and leaving dairy farms. If these practices are followed, the opportunity for the virus to enter new herds should be greatly reduced.

Birds also carry the virus. Their easy access to feed and water on dairy farms makes them more difficult to control. State and federal fish and game departments and wildlife agencies work with farmers to reduce the risk of diseases spread by wild birds. These include programs to limit the number of birds attracted to dairy farms while at the same time complying with rules that protect these species.

Producers who observe cows with clinical signs of avian influenza should notify their veterinarians so that appropriate testing can be performed to confirm the presence of avian influenza. If a test result is positive, the laboratory performing the test must report it to the USDA. As USDA and affected states continue to track the disease, an accurate estimate of the affected farms will allow investigators to determine how the virus is spreading from farm to farm—and whether we’re making progress in keeping the disease.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jason Lombard, Colorado State University

Read more:

Jason Lombard receives funding from the USDA. He is affiliated with the National Mastitis Council and the American Association of Bovine Practitioners. He is a former USDA employee.