NASA’s critical mission in the search for life beyond Earth, the Mars Sample Return, is in trouble. Its budget has increased from US$5 billion to over $11 billion, and the sample’s return date could slip from the end of this decade to 2040.

The mission would be the first attempt to return rock samples from Mars to Earth so that scientists can analyze them for signs of past life.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said during a press conference on April 15, 2024, that the mission as currently conceived is too expensive and too slow. NASA gave private companies a month to submit proposals to return the samples in a faster and more affordable way.

As an astronomer who studies cosmology and has written a book about early missions to Mars, I have been watching the sample return saga play out. Mars is the closest and best place to search for life beyond Earth, and if this ambitious NASA mission were to materialize, scientists would miss the opportunity to learn much more about the red planet.

The habit of Mars

The first NASA missions to reach the surface of Mars in 1976 revealed the planet as a frigid, uninhabitable desert without a thick atmosphere to protect life from the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation. But studies conducted in the past decade suggest that the planet may have been much warmer and wetter several billion years ago.

The Curiosity and Perseverance rovers showed that the planet’s early environment was suitable for microbial life.

They found the chemical building blocks of life and signs of surface water in the distant past. Curiosity, which landed on Mars in 2012, is still active; its twin, Perseverance, which will land on Mars in 2021, will play a critical role in the sample return mission.

Why astronomers want samples of Mars

NASA first looked for life in Mars rock in 1996. Scientists claimed to have found microscopic fossils of bacteria in the Mars meteorite ALH84001. This meteorite is a piece of Mars that landed in Antarctica 13,000 years ago and was discovered in 1984. Scientists have disagreed about whether the meteorite ever actually had life, and most scientists today agree that it did not. enough evidence to say that there are fossils in the rock.

Hundreds of Martian meteorites have been found on Earth in the last 40 years. They are free samples that fell to Earth, so although they seem intuitive to study, scientists cannot say where on Mars these meteorites came from. Also, they were blasted off the surface of the planet by impacts, and those violent events could easily destroy or alter subtle evidence of life in the rock.

Samples cannot be brought back from a region known to have welcomed life in the past. As a result, the agency is facing a price tag of $700 million per ounce, making these samples the most expensive material ever collected.

A very strong and complex mission

Returning Mars rocks to Earth is the most challenging mission NASA has ever attempted, and the first step has already begun.

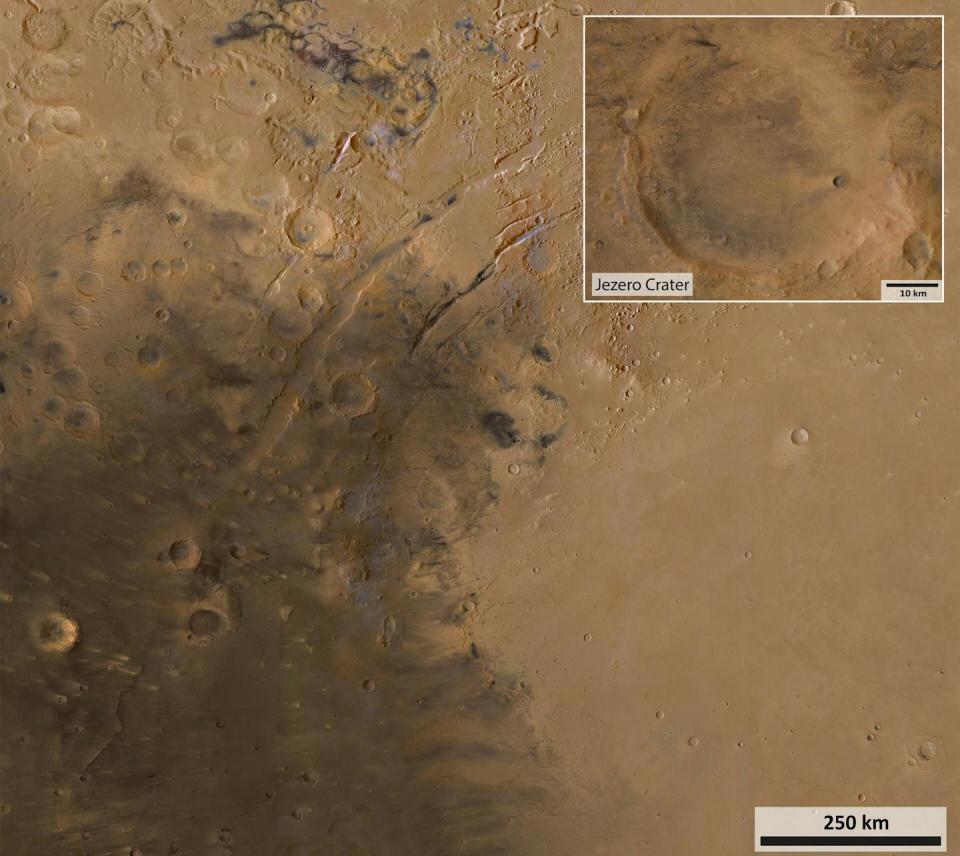

Perseverance has collected over two dozen rock and soil samples, depositing them on the floor of the Jezero Crater, a region that was probably once flooded with water and could support life. The rover places the samples into test tube-sized containers. When the rover fills all the sample tubes, it will collect them and take them to where NASA’s Sample Recovery Lander will land. The Sample Recovery Lander includes a rocket to put the samples into orbit around Mars.

The European Space Agency has designed an Earth Return Orbiter, which will launch the rocket into orbit and capture the basketball-sized sample vessel. The samples will then be automatically sealed into a biocontainment system and transferred to an Earth entry capsule, which is part of the Earth Return Orbit. After the long journey home, the entry capsule will parachute to the Earth’s surface.

The complex choreography of this mission, which includes a rover, a lander, a rocket, an orbiter and the coordination of two space agencies, is unprecedented. It is the culprit behind the ballooning budget and the long timeline.

A sample return breaks the bank

Mars Sample Return has blown a hole in NASA’s budget, threatening other missions that need funding.

The NASA center behind the mission, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, has just laid off more than 500 employees. The layoffs were likely partly due to the Mars Sample Return budget, but they also came down to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory after a plate full of planetary missions and suffering budget cuts.

In the past year, an independent review board report and a report from NASA’s Office of Inspector General have raised serious concerns about the viability of the sample return mission. These reports described the mission design as overly complex and noted issues such as inflation, supply chain problems and unrealistic cost and schedule estimates.

NASA is also feeling the heat from Congress. For fiscal year 2024, the Senate Appropriations Committee cut NASA’s planetary science budget by more than half a billion dollars. If NASA can’t keep the costs covered, the mission might even be canceled.

Thinking out of the box

Faced with these challenges, NASA has called for innovative designs from private industry, with the goal of reducing the cost and complexity of the mission. Proposals are due by May 17, which is a very tight timeline for such a challenging design effort. And it will be difficult for private companies to improve on the plan that took over ten years to put together by experts at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

A potentially important player in this scenario is the commercial space company SpaceX. NASA is already partnering with SpaceX on America’s return to the Moon. For the Artemis III mission, SpaceX will attempt to land humans on the Moon for the first time in over 50 years.

However, the massive Starship rocket that SpaceX will use for Artemis has only had three test flights and needs much more development before NASA will trust it with human cargo.

In principle, a Starship rocket could return a large load of Mars rocks in a single two-year mission and at a much lower cost. But Starship comes with great risks and uncertainties. It is unclear whether that rocket could return the samples already collected by Perseverance.

Starship uses a launch pad, and needs to be refueled for a return trip. But there is no launch pad or fueling station at the Jezero Crater. Starship is designed to carry people, but if astronauts go to Mars to collect the samples, SpaceX will need a Starship rocket that is even bigger than the one it has tested so far.

Sending astronauts involves additional risk and cost, and a human deployment strategy may be more complex than NASA’s current plan.

With all these pressures and constraints, NASA chose to see if the private sector can come up with a winning solution. We will know the answer next month.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Chris Impey, University of Arizona

Read more:

Chris Impey receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.