The American philosopher Daniel Dennett, who has died at the age of 82, was, along with Richard Dawkins, one of the biggest proponents of Darwinism and one of the fiercest controversies in the academic circuit.

Dennett argued that everything must be understood in terms of natural processes, and that terms such as “intelligence” “free will”, “consciousness” “justice”, the “soul” or the “self” describe phenomena that can to be explained in terms of physical processes and not the exercise of some disembodied or metaphysical power. How such processes work he considered an empirical question, to be answered by looking at neuroanatomy – the engineering of the brain.

Darwinism, for Dennett, was the great unifying principle that explains how the simplest organisms evolved into humans who can theorize about the kinds of creatures we are. In Consciousness Explained (1991), he argued that the term “consciousness” only describes “dispositions to behave” and that the idea of ”self” was only a “narrative center of gravity”.

In Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995) he went further than any other philosopher or biologist in claiming that the whole of nature, including all individual human and social behaviour, is underpinned by a Darwinian “algorithm”, – a single arithmetic, computational routine.

Taking into account Richard Dawkins’ concept of “memes” (“packages” of transferable cultural ideas that include anything from belief in God to an individual’s fashion taste), Dennett argued that a Darwinian algorithm also explained, for example, musical genius JS Bach, whose brain was “exquisitely designed as a program for composing music”.

Dennett’s philosophy suffers from any idea of teleology or “objective” creation. There is no point in our existence, he claimed, and those who believe otherwise put their faith in “skyscrapers” (“hooks” that can be stuck in the sky to make it easier to build skyscrapers). Of course, there are no Skyhooks, but, Dennett argued, men reach for a piece of magic, a designer behind the design, so that life has no intrinsic meaning.

On the other hand, he called Darwinians the “brights”, a group he tended (in the American context, perhaps) to see as an oppressed minority.

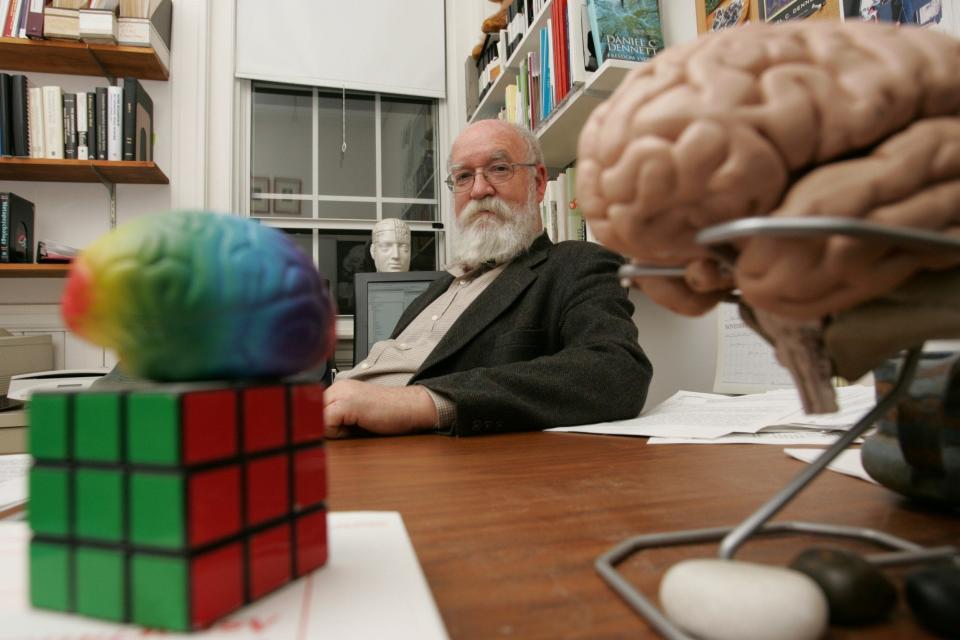

Dennett was not a man who shied away from conflict. On the door of his office at Tufts University, Boston, Massachussetts, he pasted Gore Vidal’s comment: “It is not enough to succeed; others must fail.” His targets included most of the great names in the recent history of thought – John Searle, Noam Chomsky, George Steiner, Stephen Jay Gould, Roger Penrose, Jerry Fodor, Richard Lewontin – all merchants “skyhook”, in Dennett’s opinion.

Gould was a particular target, a man who was strongly opposed to the evolutionary psychology that Dennett was promoting. In Darwin’s Dangerous Idea Dennett devoted four chapters to demolishing Gould.

But Dennett’s closest judgment was reserved for peddlers of religion who, like Dawkins, he believed to be a “meme” every bit as dangerous as the AIDS virus. In Breaking the Spell (2006) he tried to show that religion itself is a biologically developed concept, and that it is a concept that is still less useful.

Dennett’s opponents pointed out that, while maintaining his view of the evolutionary origins of religion, Dennett was just as closed to opposing views as any religious founder. Indeed he with his white beard and mustaches looked something of a 17th century Ranter. There were also those who thought directly about the scientific evidence he had to support his arguments.

Dennett argued that religion is subject to the “laws” of evolution – such as natural selection. Embracing the idea of religion as a self-propagating “meme” that changes as it is passed down through generations of human “hosts”, he has staked his reputation on an idea for which there is no supporting data.

Asked how he could be so confident, Dennett replied: “It helps to be right, I guess”.

Daniel Dennett was born in Beirut on 28 March 1942 into an established English family. His father, Daniel Dennett senior, was a distinguished historian who specialized in the social and political history of Islam. When his son was born he had transferred from Harvard to the University of Beirut to complete his doctorate. When America entered World War II, he was recruited as the CIA’s predecessor in the Middle East. He was killed in a plane crash while on a mission to Ethiopia in 1948 when his son was five years old.

The family – his mother, Daniel, and two sisters – returned to New England. “I grew up in the shadow of everyone’s memories of a legendary father,” Dennett said. “Everyone assumed that I would eventually go to Harvard and become a professor.”

After receiving his education at Phillips Exeter Academy, he went to Wesleyan University, where, in his first year, he took a paper on mathematical logic and lore on WVO Quine’s From a Logical Point of View (1953). He disagreed with Quine, but he was so interested that he immediately wrote to Harvard, where Quine was teaching, asking for a transfer. “I thought I’m going to be a philosopher and… tell this guy Quine why he’s wrong,” Dennett said.

After graduating from Harvard, Dennett went on to Oxford as a graduate student, where Gilbert Ryle, who had been warned by Quine, found him a place at Hertford College. Curiously enough, the strongest impression Dennett made at Oxford had little to do with his academic talents. As well as being a talented sculptor, he supplemented his allowance by playing jazz piano in bars and claimed to have introduced the first Frisbee to Britain and seen his meme colonize the country.

Although at Harvard he was seen as a critic of Quine, at Oxford he was seen as “the village Quinean”. It was at Oxford, too, that he first became interested in the functioning of the brain.

Oxford philosopher John Lucas published a paper arguing that Godel’s incompleteness theorem disproved the suggestion that human brains function like machines or that human thought could be completely simulated by a computer. Dennett effectively spent the rest of his life challenging this view.

When Dennett, aged 23, returned to America and his first job – at the University of California at Irvine – his thoughts were almost complete. A version of his doctoral thesis was published in 1969, as Matter and Consciousness; his next book, Brainstorms (1978), was the first full statement of his distinctive approach to the behavior of the brain and its relationship to philosophical concepts.

In 1971 Dennett moved to Tufts University where he resigned as professor and chairman of the philosophy department and, since 85, director of the Center for Cognitive Studies. During the 1970s and 1980s he made two friendships that would greatly affect his work – with Richard Dawkins, who published Selfish Gene in 1976, and with Douglas Hofstadter, the computer scientist who wrote Godel, Escher, Bach (1979) , a classic work. on artificial intelligence.

Towards the end of the 1970s, Dennett spent a year at Stanford with Hofstadter and they collaborated on the anthology, The Mind’s I (1981), which remains, with his collection of essays, Brainchildren (1998), the clearest statement of Dennett’s thought.

Although Dennett’s books are compact, they have sold very well. In Freedom Evolves (2003) he argued that people with genes that predispose them to, say, alcoholism or criminality are not capable of becoming alcoholics or criminals, because they also have evolutionarily determined free will. “Free will is like the air we breathe, and it is present almost everywhere we want to go,” he argued, “but it is not only eternal, it has evolved, and is still change.”

Daniel Dennett married, in 1963, Susan Bell, with whom he had a son and a daughter.

Daniel Dennett, born 28 March 1942, died 19 April 2024