Frontotemporal dementia is one of the most common forms of dementia that strikes before the age of 65. Although symptoms usually begin in the late 60s, it can strike as young as 30 or as old as 90.

The good news is that this is the fastest-moving area of research in the dementia space and has high hopes for effective treatments on the horizon. So what is it and why could we be on the verge of a breakthrough?

What is frontotemporal dementia (FTD)?

“It is a group of illnesses marked by damage and shrinkage in the frontal and temporal areas of the brain,” says Dr Teresa Niccoli from the Institute of Healthy Aging at UCL. The temporal lobes are behind the ears and the right frontal lobe is at the front, just behind the forehead.

What are the symptoms of FTD?

Personality and behavior changes

“The front part of the brain gives us so much of our personality, our social knowledge and our behavior, our motivation and our impulse control,” says James Rowe, professor of cognitive neurology and chairman of Alzheimer’s scientific advisory board Research UK. “It stores all the deep knowledge we learn about how to behave, how to be social and what is normal.” Symptoms of damage to the frontal lobes include:

Language changes

“The temporal lobes are where our language centers are based,” says Professor Rowe. “Damage here can mean we lose the ability to produce speech, and also lose the deeper understanding of what words and things mean (called semantics).

Symptoms include:

-

Fragmented, labored speech

-

Inability to recall the meaning of certain words (‘What is ‘lemon’?’ ‘What is ‘tin’?’)

-

Inability to understand what a common object is or how it is used (for example, what foods are most edible, how to use a kettle, what to do with a whisk)

FTD stages: from speech stoppage, weakness and loss of balance

The progression of the disease is different for everyone and depends on many factors, including the type of FTD; if there is a genetic mutation; age of onset and the areas of the brain most affected.

“It often progresses slowly but steadily,” says Professor Rowe. “While it can be very dramatic, upsetting and challenging to live with in the early years, over time, withdrawal tends to increase.

“Language and communication dry up slowly. At first the spontaneity is reduced, and later the speech usually stops altogether.

The weakness also increases. There are often problems with mobility and balance and increased nursing needs.

“The last days of life are usually calmer, if managed well – for example by slipping into sleep. It is very important to maintain the quality of life in the earlier years.”

The average survival time after diagnosis is seven to eight years but this is highly variable, between one year and 15 years.

What causes FTD?

Three gene mutations are thought to cause about a third of all cases. “Unlike many other dementias, this is largely genetic,” says Dr. Nichols.

In the other two thirds, there are several theories. One is that it is still genetic – but caused by our own unique disturbance of genes, which is not yet understood. Another is that it is a slight defect in the brain’s “waste disposal system”.

“The brain is constantly getting rid of waste proteins and all it takes is a slight imbalance to stop clearing the waste proteins completely every day, to start a very slow build up,” says Prof Rowe. Research shows that changes in the brain can begin quietly and gradually 25 years before symptoms begin.

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosis should begin with an in-depth conversation between the patient, the patient’s family and a specialist, such as a neurologist or psychiatrist, who knows what to look for.

“It’s almost all in history – the story of change, the pattern that the person shows is clearly different from who they once were,” says Professor Rowe, who runs specialist clinics for people with FTD.

A brain scan can then confirm the diagnosis, and a genetic test will identify whether a person’s illness is due to one of the genetic mutations.

Although the language variations of FTD are usually diagnosed earlier, the correct diagnosis can take several years when the main symptoms are behavioral changes. “It’s often misdiagnosed as depression, stress or relationship problems at first,” says Professor Rowe.

What are the treatment options?

-

Medicines

-

Antidepressants

-

Physiotherapy, speech and language therapy

-

Early stage gene neutralization technology

“Treatment needs to be tailored and personalised,” says Professor Rowe. “There are many medications that can help with symptoms – whether it’s related to mood, anxiety and agitation, hallucinations, obsessive or sexual behavior or disturbed sleep.”

SSRI antidepressants can be useful for a wide range of behavioral symptoms. “There is also scope for physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, and psychological support for the family – everything is important. They can be accessed by referral from a GP or memory clinic. There are private providers in many areas for self-referral, but there are also NHS services in most areas.”

Although there are currently no disease-modifying treatments to stop FTD, Professor Rowe believes there may soon be, at least for the genetic variants. “We’re on the brink of a revolution here,” he says.

“There are multiple trials currently underway that use different techniques to neutralize the faulty genes that cause FTD. The background light looks very strong.”

These techniques include a new “designer virus” to deliver replacement genes, or designer antibodies and drugs that block the faulty gene. These current technologies must be given by drip, or injection, or operation, but perhaps tablets in the future.

Gene neutralization technology is already licensed for the devastating childhood illness spinal muscular atrophy and appears to stop the illness in its tracks.

“We should start to see the results of FTD in the next year or two,” says Professor Rowe. “Not all of them will work, but the rate of progress is so fast, that we can be optimistic. In principle, after that, it would also be possible to treat family members who have the gene but without any symptoms. That would mean the cards are also banned.”

What is the difference between FTD and Alzheimer’s?

The main difference is the brain region that is affected and causes different symptoms. Alzheimer’s usually starts in the memory centers before spreading to most areas of the brain, and FTD is more specific. “With FTD, the first neurons you lose are related to ‘personality and behaviour’ or ‘language’,” says Dr Niccoli.

When Hollywood actor Bruce Willis, 67, was diagnosed with FTD, the Alzheimer’s Association website saw a 12,000 percent spike in traffic.

Support for families with FTD

“The stress and impact of FTD can be alleviated if families are helped to understand the disease and what is driving the difficult, distressing and embarrassing behaviours,” says Professor Rowe. “Just hearing: ‘We know what this is, we’ll help you deal with it and put you in the driving seat,’ can be a relief.”

Families may need help to devise strategies to cope with certain behaviours, to understand triggers, to reduce stress, to develop diversion techniques and perhaps to find new ways of communicating, through gestures, drawings or electronic devices.

“Practical help such as relief, and financial advice about benefits and early pensions can also make a big difference,” explains Professor Rowe.

“The person with FTD often feels very good and very happy; Our job is to maintain that sense of quality of life, and help the family manage the challenges” Families can be supported by memory clinics, local branches of the Alzheimer’s Association, and the support group FTD among others.

“At first, you’re shocked and upset. It’s ‘progressive’, ‘incurable’, your life will never be the same”

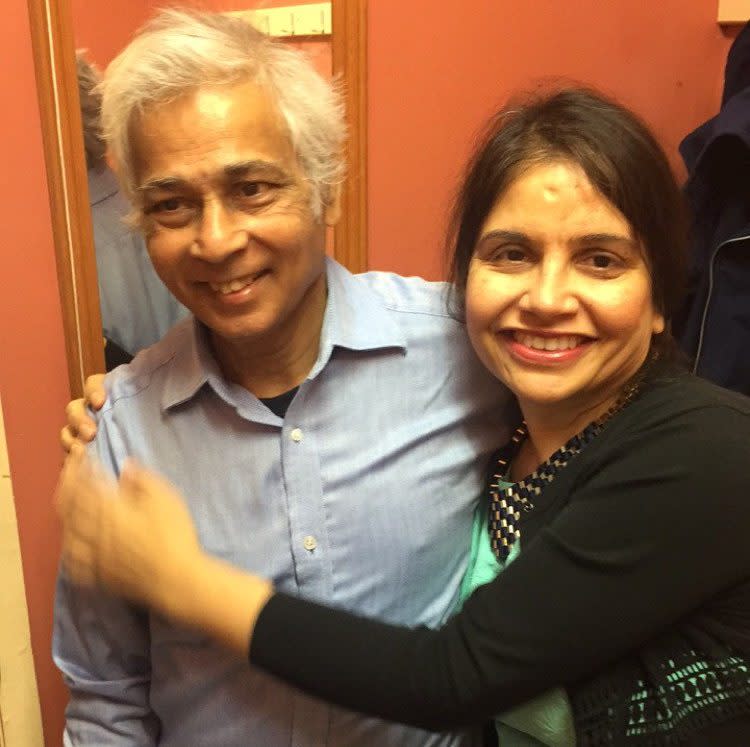

The first clear sign that something was very wrong with Urvashi Desai’s husband Bhupendra was when he turned to her and told her that he did not have their three sons. “I didn’t know what he meant. He loved his boys, he loved me, we had a great marriage. I asked him: ‘Who is her son then?’ He said: ‘I have no idea, but I have checked their passports and they are not mine’.”

Bhupendra was in his early 50s at the time – he is 69 now. His behavior was becoming more erratic. “He wouldn’t know what a packet of crisps is,” says 60-year-old Urvashi. “If I asked him to give me a lemon, he wouldn’t know where to look. He was clearly struggling writing everything down to try to keep up with reality – the number of buses, bills.

Although he had several jobs – as a support worker, in retail, in a hotel – he left them all.

“He was vibrant and alive, but withdrawn and paranoid, locked in a room with a notebook and obsessed with his Rubik’s Cube,” says Urvashi. “His life became narrower, like a funnel.

“Gradually, all the balloons that made up his life – work, friends, interests – went ping, ping, ping, until there was nothing left but family,” she says.

When Bhupendra was 56, Urvashi managed to get a proper, detailed consultation and assessment, including a brain scan. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) was the dreaded diagnosis.

It took some time for Urvashi, the former HR director of the City, to build a new life. She has scaled back her career to become an executive coach, and for the past two years, has had the help of a carer four times a week. “At first, you’re shocked and upset. It’s ‘progressive’, ‘incurable’, your life will never be the same,” she says.

“I went on a mission, looking for a cure but I moved on from that very quickly. Counseling helped me. Now I have one burning question: ‘How can I enrich my husband’s life?’

“He likes coffee shops and walking, so we do that a lot,” she continues. “We will visit museums and galleries and parks about five times a week.

“Sometimes he could behave in a challenging way and people could stare. Maybe they’re inspired by me, or maybe they’re judging me – either way, I don’t care.”

Although Bhupendra has not spoken for the past two years, Urvashi can see when he is happy and this is her guide. “He’s still the pilot of my plane,” she says. “He loves music – which he’s never done before – so we listen to a lot of music and I sing to him. Love, energy and kindness are powerful instruments that everyone can use. It’s about turning this into something worth living for – because if he’s happy, I’m happy.”

If you or someone you know has dementia and would like to take part in research, register your interest in dementia research here.

Recommended

‘At 51, my wife started craving sugar – we had no idea it was dementia’

Read more