The most important exhibition you will see in London this year is not at your Tates or your White Cubes, but it is located above the naval guns and spitfires and jeeps, deep within the Imperial War Museum.

Narrator: The photography by Tim Hetherington is important because it shows not only a talented war photographer, but an artist who was busy redefining what war photography was until his life was tragically cut short in 2011 at the age of 40 year old.

Hetherington’s approach was not simply to drop into war zones and shoot the blame. Instead, he was interested in the context of the conflict.

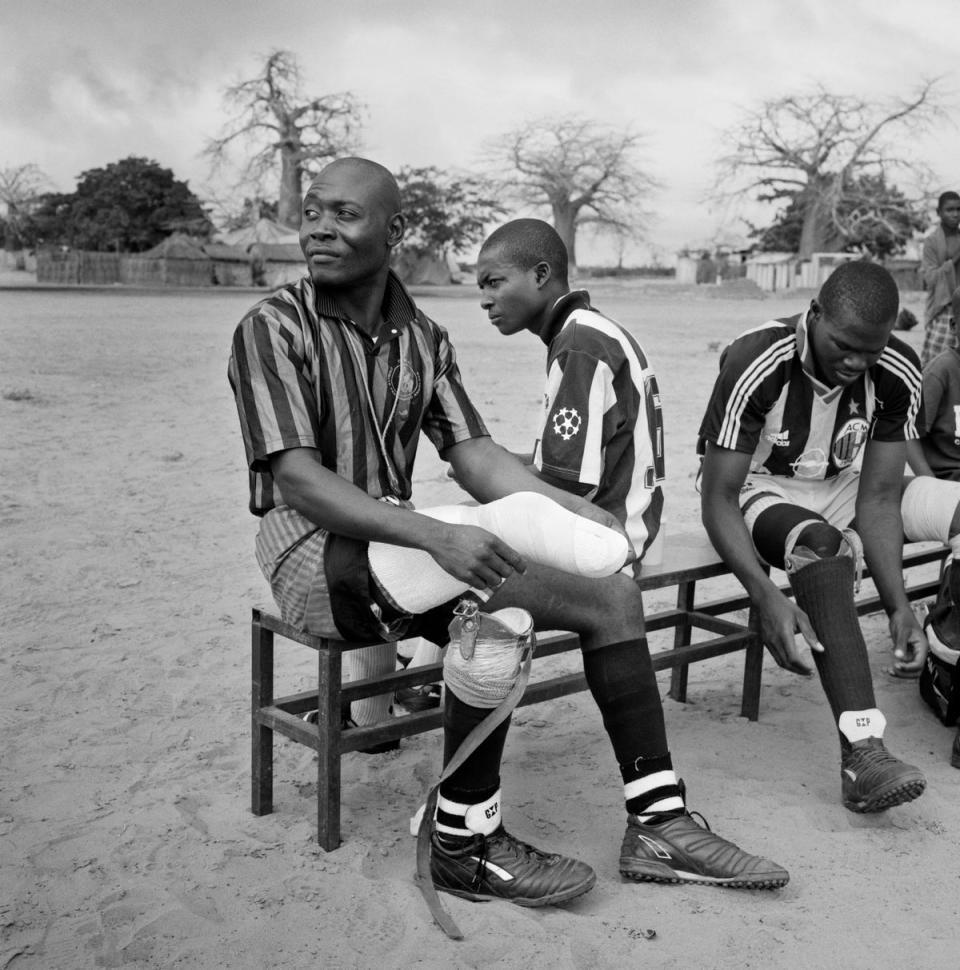

Often working in West African countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria, he would find himself in the regions long-term, to learn about society and culture and record it, seeing where comes the violence and the devastation that can follow. . He was looking for a deeper story to tell.

“War photography is often about parachuting in, capturing the drama, and then leaving,” says the show’s curator, Greg Brockett, “But Tim was more about creating long-term projects, where he would get to know the people he was photographing. It was a slow process; these projects have been added to over the years.

“He kept going back to Liberia, for example, between 2003 and 2009. He would be there for the conflict, but he would come back after it was over. His work is about people caught up in terrible conflicts. A journey through the war and its aftermath.”

If you’re familiar with Hetherington’s work, it’s probably his images of Afghanistan, commissioned for Vanity Fair. He and writer Sebastian Junger were embedded with a US Army platoon in a remote mountainside location near the Korengal Valley.

Their stunning Sundance award-winning documentary Retrepo was filmed there, footage of which is part of this multimedia experience, but the exhibition focuses on the images captured there, which are truly remarkable.

There are shots of extreme situations but this is mostly about the time of the soldiers. Cooling, wrestling, digging, and sleeping. The second series of images, a series that Hetherington also made into a film – Sleeping Soldiers – is where his work began to become transcendent. The soldiers in it are curled up sleeping in their tables and look like children. Hugging themselves, often in the fetal position, they are completely vulnerable and you can’t help but feel protected by them.

It seems a bit trite to talk about the human cost of war, but really, that’s what Hetherington got across, better than anyone. These are young people with real bodies that have been put on the line for political decisions made far away. We are reminded of life dealing with the nearness of death.

“Through their commitment to spending so much time with the soldiers, they started to feel like part of the gang,” says Gregg, “which allowed Tim to take photographs in a more natural way. He becomes interested in the bonds they have created together as a group.

The work is not really about the conflict itself, but how the bonds develop and how people behave in these environments. It is much more about the anthropological behavior of people. And they are very connected portraits of people.”

This is anti-war photography like you’ve never seen before. It’s not anti-troops, it’s about the cost of war, the soldiers and the people left picking up the pieces. And it’s brilliantly presented in this exhibition in a way that makes you want to follow the story.

The exhibition is put together to give a sense of immersion in the places he visited. Some of his images are blown over entire walls, giving the effect of placing you right in the locations But the images don’t need it either – Hetherington’s amazing work is so big right now, it’s like traveling through time and space. space where you are. he can feel the heat as well as the fear.

In the age of the endless scroll of doom, when images have little meaning because of their intensity, it feels strange to be reminded of the power of photography when presented in this way. Gregg says, “The way we treat social media images is an antithesis. This is a long look, a nuanced look, not one you scroll past in two seconds. it brings out the human factor.”

Hetherington’s diaries are also on display, with extracts from them on the walls along with a more detailed look inside them on interactive screens. These are significant documents in that they are not just action recordings, but a collection of his thoughts on his approach to photography and his own role as a photographer. His writing is much closer to John Berger’s Ways of Seeing than Michael Herr’s Dispatches.

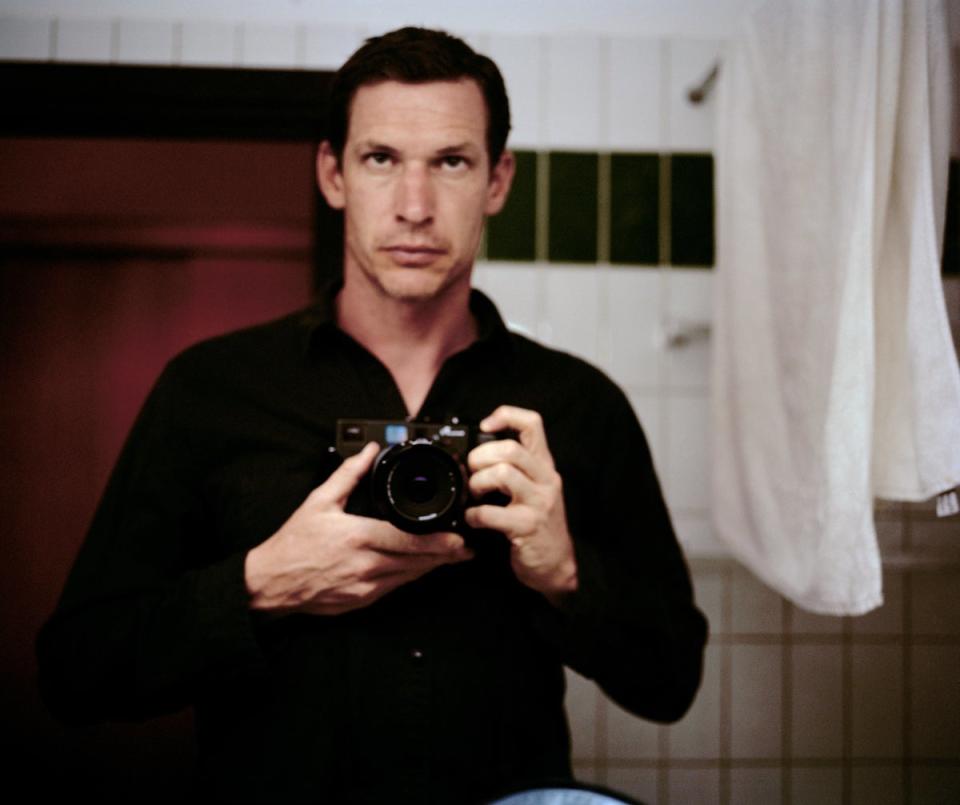

Hetherington was a deep thinker, and it was clear that his reflection on his own role was shaping his work towards the end – in a way that would now be called meta but was then postmodern. He was interested in how his presence as a man with a camera was affecting the environments he was in, and creating performances in his subjects. What is reality? We humans tend to live in the lines between reality and fabrication.

“We wanted to highlight where he was going with his work,” says Gregg, “which was very much about including himself in his work. To try to understand what drew him. And what is the role of the image maker in all of this.”

Sadly, Hetherington’s moves in this direction did not materialize. Hetherington was killed by an explosion in Libya during the civil war in 2011. His group was traveling with rebel fighters at the time, and Hetherington died from blood loss along with fellow photographer Chris Hondros.

It was a tragic end but as the years go by, his work continues to grow, and this exhibition is another important step in immortalizing his work. It is not to be missed.

Narrator: Photography by Tim Hetherington’ at IWM London from 20 April to 29 September.