-

The leafhoppers are the only species that secrete brochosomes: rare nanoparticles with invisibility properties.

-

But for the first time, a group of scientists have created their own synthetic brosis.

-

They hope that their brosomes will one day be used for invisible coating devices and other technologies.

We tend to think of invisibility blankets as science fiction. But one group of scientists has taken a big step to make them a reality.

For the first time, scientists at Pennsylvania State University have created synthetic replicas of chromosomes, naturally occurring nanoparticles that could one day be used to make invisibility cloaking devices.

The invisibility cloak is not the only application of synthetic bromosomes. In the next few years, they could find their way into a range of commercial applications—from solar energy to pharmaceuticals, according to lead researcher Tak Sing Wong, a professor of mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering at Penn State.

Solving a 70-year-old geometric mystery

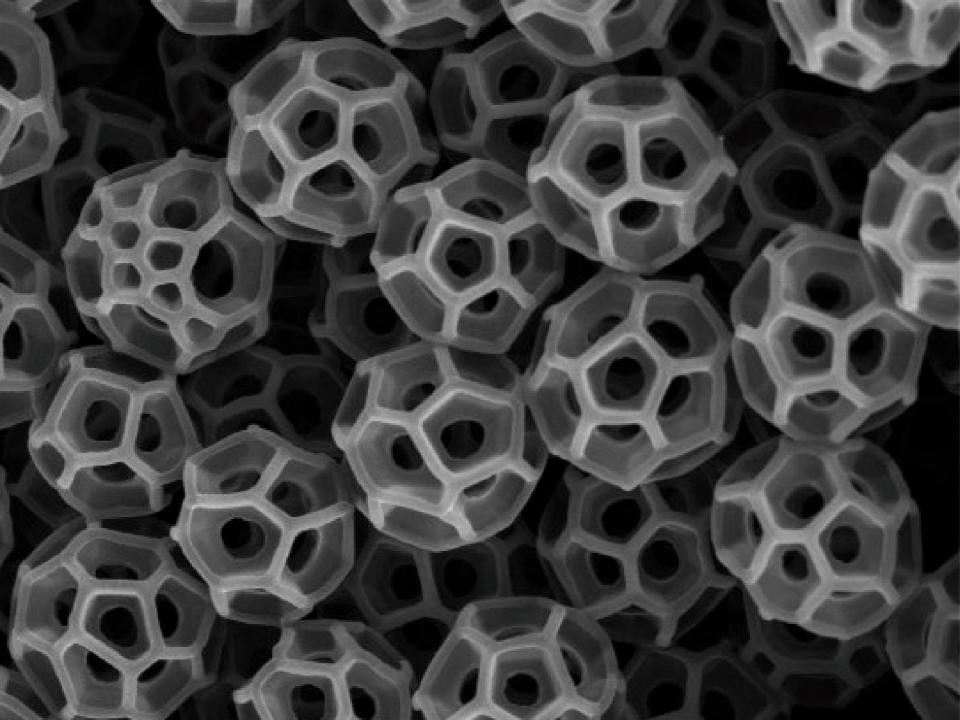

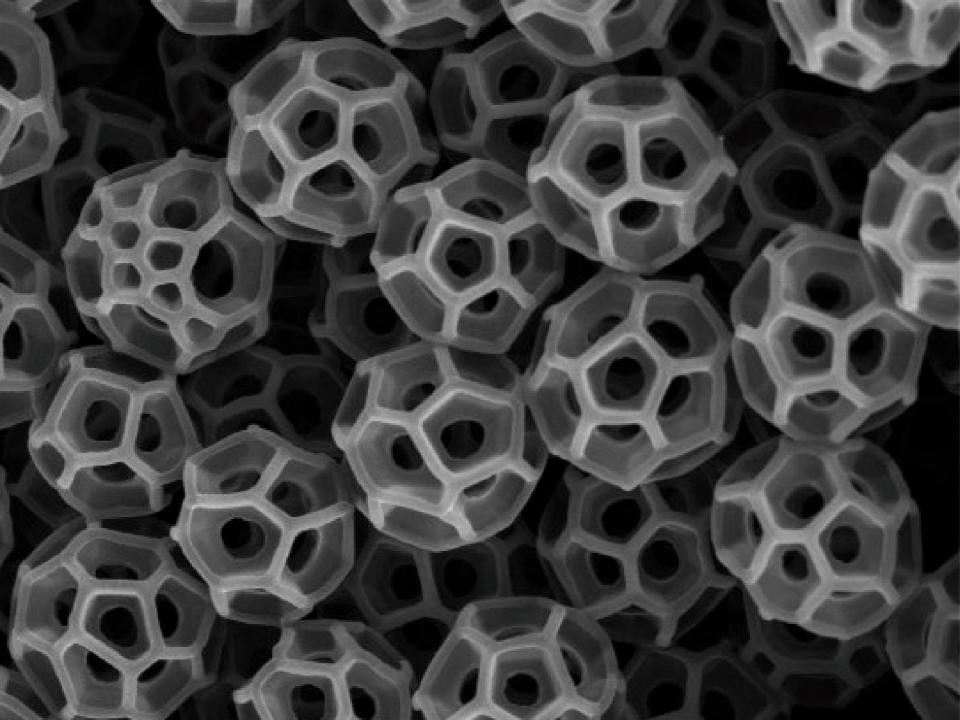

They are curved nanoparticles in the shape of a bucky ball and covered in holes — called holes — that go all the way through them. This complex structure allows them to absorb or scatter certain wavelengths of light, depending on the size of the brochure and its holes.

The only place in the world where you can find naturally occurring brochosomes is on the back of a leaf – a common backyard insect. Their broccoli coats were first discovered in the 1950s, and probably help them blend into their surroundings.

Scientists are not entirely sure why chromosomes secrete and coat themselves. Until now, they did not even understand the purpose of the complex geometry of nanoparticles.

“This is really the first study to understand how the complex geometry of the brochure interacts with light,” said Wong.

To achieve that understanding, Wong and his colleagues had to figure out how to replicate a brochure. After nearly ten years of research, they succeeded in 3D printing the world’s first synthetic chromosomes.

Invisibility properties of bromosomes

Brocosome geometry has two important aspects: the diameter of the particle, and the diameter of its pore.

If the wavelength of light is the same length as the diameter of the bromosomes, it will be scattered in all directions when it hits the particle. But if the wavelength of the light is as long as the diameter of the three-hole brosome, it will pass through the particle and be absorbed.

This absorption combined with light scattering means that brochosomes have very limited light reflection – and can be invisible over certain electromagnetic ranges. Covering an object in them could, in theory, act as a cloak of invisibility.

The beauty of synthetic bromosomes is that they could be made in different sizes, and thus adapted to absorb and transmit different wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum. That means engineers can tailor bromosomes for specific applications, such as invisibility to infrared radiation to aid in military defense.

In fact, Wong’s bromosomes are just the right size to do just that. They are about 40 to 50 times larger than naturally occurring ones, and they only interact with infrared radiation. Wong’s future research will focus in part on making smaller synthetic broxosomes to focus on the shorter end of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The commercial potential of bromosomes

Although Wong’s synthetic bromosomes are a big step toward invisibility-cloaking technology, scientists are still decades away from bringing anything to market.

“I think in my life, it is possible,” said Hao Xin, a professor of electrical and computer engineering and physics at the University of Arizona who were not involved in the study. It will take at least 50 years, he said.

But in three to five years, Wong hopes to produce bromosomes on a large enough scale to be used in pigments, pharmaceuticals and solar panels.

For example, the European Union recently banned titanium oxide, a white pigment used in everything from candy to sunscreen, as a food additive. Wong believes that brochosomes could eventually replace titanium oxide in foods like candy and coffee creamers.

“Depending on our imagination, I think there are a lot of cool applications that could come out of brocosomes,” Wong said.

Read the original article on Business Insider