The CNN Original Series “Space Shuttle Columbia: The Last Flight” reveals the events that eventually led to disaster. The four-part documentary continues at 9 pm ET/PT Sunday.

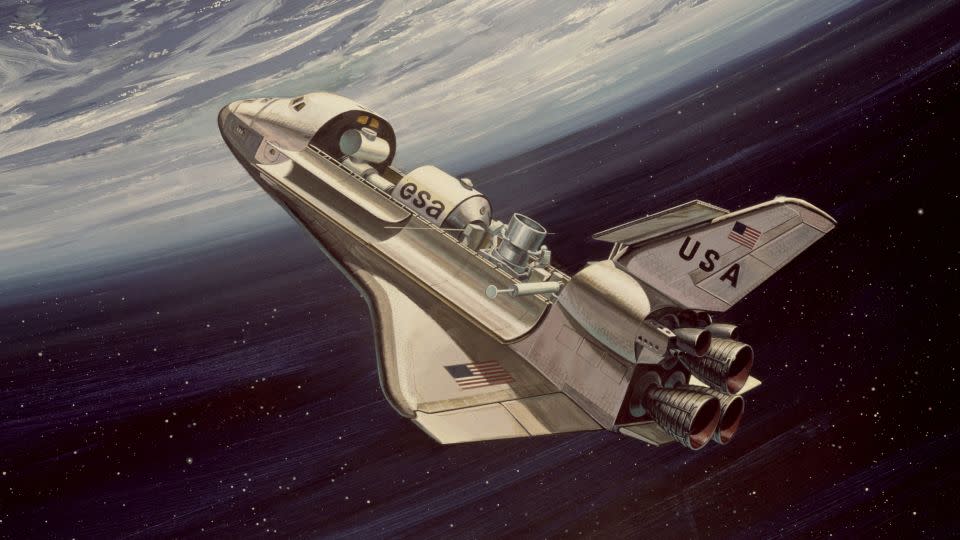

When it began, NASA’s space shuttle program promised to usher in a new era of exploration, providing space-limited astronauts with a reusable and relatively inexpensive ride into orbit. It was a project that changed the course of spaceflight forever with its triumphs — and its tragic failures.

Considered an “engineering marvel”, the first of five winged orbiters – the space shuttle Columbia – made its maiden flight in 1981.

Twenty years and 28 trips to space later, the same shuttle broke apart during its return to Earth, killing all seven crew members on board.

The tragedy ended the US space agency’s transformative shuttle program. And his memory still echoes in the halls of NASA today, leaving a lasting mark on his consideration of safety.

“Human history teaches us that when audited, after accidents like this, we can learn from them and further reduce risk, although we must honestly admit that risks can never be eliminated,” it was said then.–NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe, who ran the agency from 2001 to 2004, in a speech before members of Congress shortly after the Columbia disaster.

After the shuttle program was discontinued, no US astronaut would travel to space on an American-made rocket for nearly a decade.

Reimagining a rocket

The space shuttle project was forged in hopes of NASA’s Apollo program, which landed 12 astronauts on the lunar surface and put America ahead of its Soviet rivals during the Cold War.

Apollo, however, was extremely expensive: NASA spent $25.8 billion (or more than $200 billion when adjusted for inflation)—according to a cost analysis by space policy expert Casey Dreier of the nonprofit Planetary Society.

With financial constraints looming, by the mid-1970s, engineers within NASA were building an entirely new mode of space transportation.

Apollo used tall rockets and small capsules – destined to fly once – that flew home from space and parachuted to an ocean landing.

The space shuttle concept was a significant pivot: reusable winged orbiters attached to rockets would launch through Earth orbit and glide to an airplane runway. From there, the shuttle could be refurbished and flown again, theoretically driving down the cost of each mission.

Legacy Shuttle

Over the decades, NASA’s space shuttle fleet has flown 135 missions—launching and repairing satellites, building a permanent home for astronauts with the International Space Station and commissioning the revolutionary Hubble Space Telescope.

But the shuttle program, which ended in 2011, fell short of the US space agency’s initial vision.

Each shuttle launch costs an average of about $1.5 billion, according to a 2018 paper by a researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center. That’s hundreds of millions of dollars more than the space agency had expected since the start of the program, even when adjusted for inflation. Long delays and technical difficulties also hampered their missions.

“Every mission I’ve been on has been scrapped, rescheduled, delayed because something wasn’t quite right,” O’Keefe, the former NASA administrator, said in a new CNN documentary series, “Space Shuttle Columbia: The Final Flight . “

And two disasters – the explosion of Challenger in 1986 and the loss of Columbia in 2003 – cost the lives of 14 astronauts.

The Columbia disaster: Looking back

On the morning of February 1, 2003, the orbiter Columbia was heading home from a 16-day mission to space.

The seven-person crew on board performed numerous science experiments while in orbit, and the astronauts landed at 9:16 a.m. ET in Florida.

unknown content item

–

NASA engineers knew that a piece of foam – used to insulate the shuttle’s large orange fuel tank – had broken off during the January 16 launch, hitting Columbia’s orbiter.

However, the space agency’s position was that the light insulating material was unlikely to have caused significant damage. Some foam broke out on earlier missions and caused minor damage, but was considered an “acceptable flight risk,” according to Columbia’s official accident investigation report.

However, it was later revealed that NASA management was concerned about the impact of the foam being swept under the carpet, according to previous reporting and “Space Shuttle Columbia: The Final Flight”.

“I was very upset and angry and disappointed with my engineering organizations, from top to bottom,” said Rodney Rocha, NASA’s chief shuttle engineer, in the new series.

The astronauts even received an email from mission control alerting them of the foam strike on the eighth day of their mission, assuring them there was no cause for alarm, according to NASA.

But the assumption was wrong.

A later investigation revealed that the dislodged foam hit Columbia’s left wing during launch, damaging the spacecraft’s thermal protection system.

Crew members were not bothered by the issue and spent more than two weeks in space.

But heat protection is key to a dangerous return home. As with all missions that return from orbit, the vehicle had to plunge back into the thick of Earth’s atmosphere while still traveling at more than 17,000 miles per hour (27,359 kilometers per hour). The pressure and friction on a spacecraft can heat the exterior to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,649 degrees Celsius).

Reentry was too much for the damaged Columbia shuttle. As the vehicle neared its destination, crossing over New Mexico into Texas, the orbiter began to decay – visibly shedding debris.

At 8:59 am ET, ground controllers lost contact with the crew.

The final address came from mission commander Rick Husband, who said, “Roger, uh,” before being cut off.

At 9 am, onlookers saw Columbia explode over East Texas and watched in horror as she littered the area with debris.

The realities of risk

Two decades later, the Columbia tragedy and the broader shuttle program provide a critical perspective on the perils and triumphs of spaceflight.

NASA entered the era with confidence, expecting the chance of a shuttle being destroyed in flight to be about 1 in 100,000.

The space agency reassessed that risk, estimating after the Challenger disaster that the shuttle had a 1 in 100 chance of disaster.

“If someone told me, ‘Hey, you can go on this roller coaster ride, and there’s a 1 in 100 chance you’re going to die. Well, there’s no chance on earth — no chance in hell — that I would do that,” US Senator Mark Kelly, a former NASA shuttle astronaut, told “The Final Flight” informants.

“But I also think people generally think it’s not going to be them,” Kelly added.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com