The more scientists learn about the health risks of PFAS, found in everything from nonstick cookware to carpets to ski wax, the more these “forever chemicals” are concerned.

The US Environmental Protection Agency now believes there is no safe level for two common PFASs – PFOA and PFOS – in drinking water, and acknowledges that very low concentrations of other PFASs pose risks to human health. The agency issued the first legally enforceable national drinking water standards for five common types of PFAS chemicals, as well as PFAS mixtures, on April 10, 2024.

I study PFAS as an environmental health scientist. Here’s a quick look at the risks associated with these chemicals and efforts to control them.

What exactly is PFAS?

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. This is a large group of man-made chemicals – currently estimated to be nearly 15,000 individual chemical compounds – widely used in consumer products and industry. They can make products resistant to water, grease and stains and fire protection.

Waterproof outdoor clothing and cosmetics, stain-resistant upholstery and carpets, food packaging designed to prevent liquid or grease from leaking through, and certain firefighting equipment often contain PFAS.

In fact, studies have found that most products labeled as stain or waterproof contain PFAS, and another study found that this is true even among products labeled as “non-toxic” or “green”. . PFAS are also found in unexpected places such as high-performance ski and snowboard waxes, floor waxes and medical devices.

At first glance, PFAS sound pretty useful, so you might be wondering what’s the big deal?

The short answer is that PFAS are harmful to human health and the environment.

Some of the same chemical properties that make PFAS attractive in products also mean that these chemicals will persist in the environment for generations. Due to the widespread use of PFAS, these chemicals are now present in water, soil and living organisms and can be found in almost every part of the planet, including Arctic glaciers, marine mammals, remote communities living on maintenance diets and in 98% of. the American public.

The US Geological Survey estimates that at least 45% of the nation’s tap water now contains common types of PFAS. PFAS maker 3M, which faces a lawsuit, announced a settlement worth at least US$10.3 billion in June 2023 with public water systems to pay for PFAS testing and treatment.

What are the health risks of PFAS exposure?

When people are exposed to PFAS, the chemicals stay in their bodies for a long time—months to years, depending on the specific compound—and can accumulate over time.

Research consistently shows that PFAS are associated with a variety of adverse health effects. A review by an expert panel that looked at research on PFAS toxicity concluded with a high degree of certainty that PFAS contribute to thyroid disease, elevated cholesterol, liver damage, and kidney and prostate cancer.

Furthermore, they concluded with a high degree of certainty that PFAS also affect children exposed in utero by increasing the likelihood that they will be born at a lower birth weight and respond less effectively to vaccines, and by at the same time the development of the mammary glands of women is impaired, which may have a negative effect on the mother. ability to breastfeed.

The review also found evidence that PFAS may contribute to several other disorders, although more research is needed to confirm current findings: inflammatory bowel disease, reduced fertility, breast cancer, and increased likelihood of miscarriage and stress high blood pressure and developing preeclampsia during pregnancy. In addition, current research suggests that children exposed early are at higher risk of obesity, early onset puberty and reduced fertility later in life.

Together, this is an impressive list of diseases and disorders.

Who is regulating PFAS?

PFAS chemicals have been around since the late 1930s, when a DuPont scientist accidentally created one during a laboratory experiment. DuPont called it Teflon, which eventually became a household name for use on non-stick pans.

Years later, in 1998, Scotchgard maker 3M notified the Environmental Protection Agency that PFAS chemicals had appeared in human blood samples. At the time, 3M said that low levels of the manufactured chemical had been detected in people’s blood as early as the 1970s.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry has a toxicological profile for PFAS. And the EPA had issued health-based advisories and guidelines. But despite the long list of serious health risks associated with PFAS and a huge amount of federal investment in PFAS-related research in recent years, PFAS has not been regulated at the federal level in the United States until now.

The new drinking water standards set limits for five individual PFASs – PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS and HFPO-DA – as well as mixtures of these chemicals. The standards are part of the EPA’s roadmap for PFAS regulations.

The EPA has also proposed listing nine PFAS as hazardous substances under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, a move that worries utilities and businesses that use products or processes containing PFAS because of the cost of cleanup.

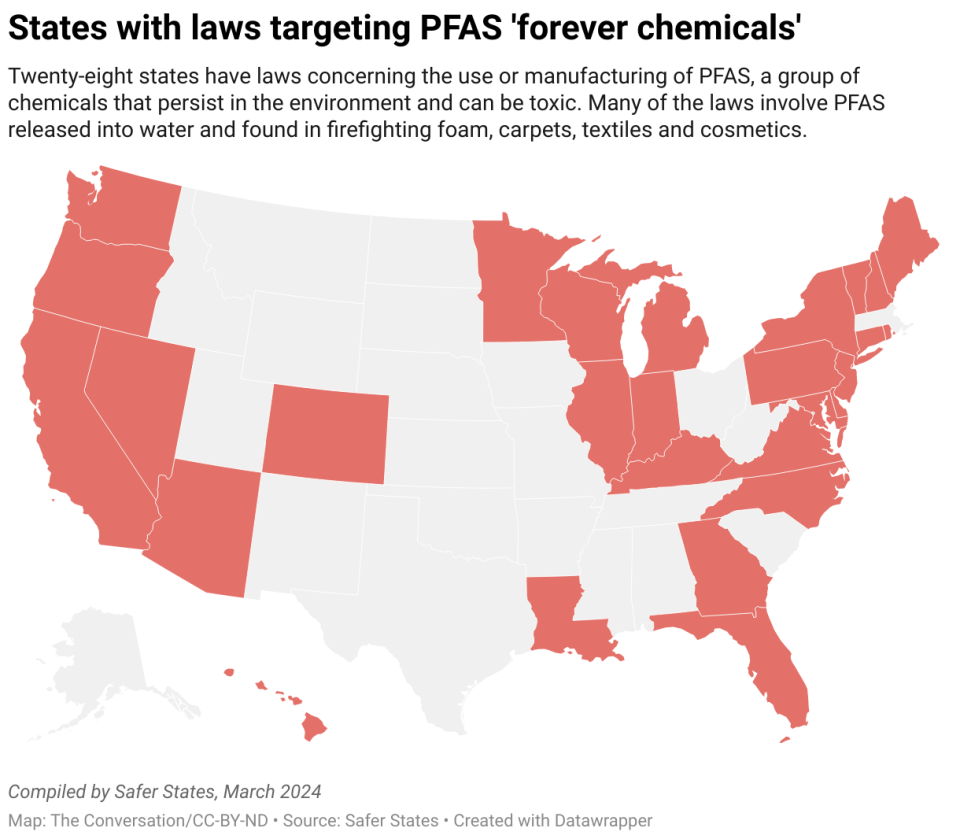

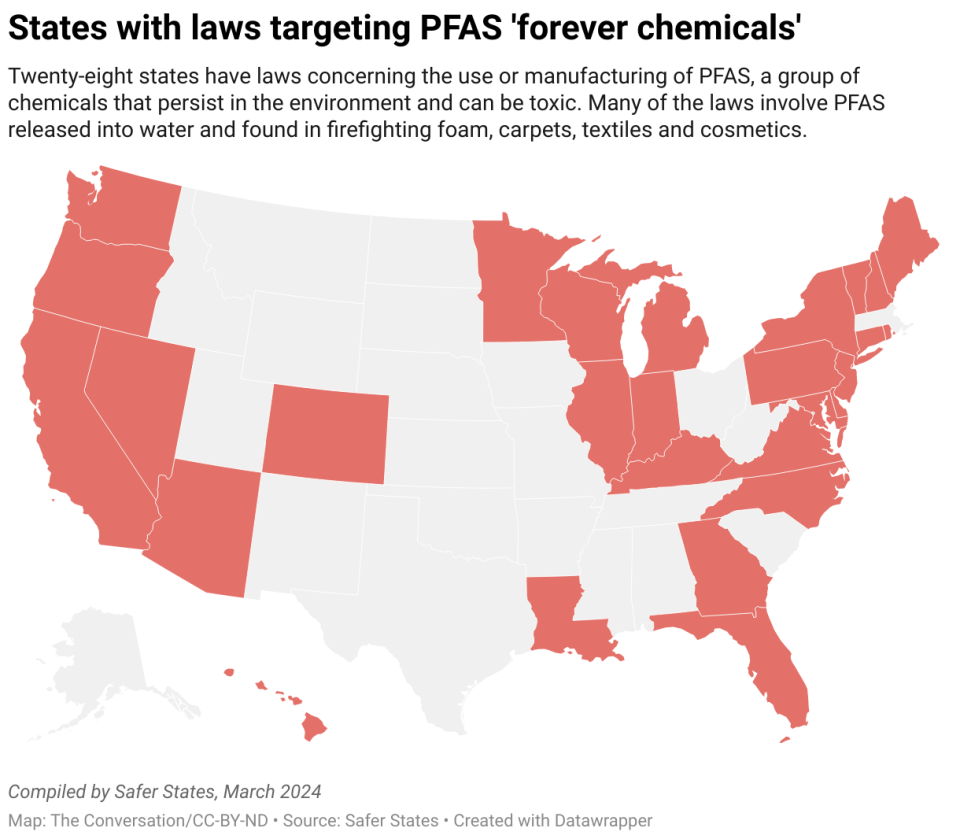

While awaiting federal action, states have taken their own steps to protect residents from the risk of PFAS exposure.

At least 28 states have laws targeting PFAS in various uses, such as in food packaging and carpets. About a dozen have drinking water standards for PFAS. But relying on state laws creates a patchwork of regulations, placing burdens on businesses and consumers to navigate regulatory nuances across state lines.

How can you reduce your PFAS exposure?

Based on current scientific understanding, most people are exposed to PFAS primarily through their diet, although drinking water and airborne exposure may be significant in some people, especially if they live near industries. or known PFAS-related contamination.

The best ways to protect yourself and your family from PFAS-related risks is to educate yourself about potential sources of exposure.

Products labeled as waterproof or stain resistant are likely to contain PFAS. Whenever possible, check the ingredients on products you buy and look for chemical names that contain “fluor-.” Specific trade names, such as Teflon and Gore-Tex, are likely to contain PFAS.

Check if there are sources of contamination near you, for example in drinking water or industries related to PFAS in the area. Strategies for monitoring and reporting PFAS contamination vary by location and source of PFAS, so the lack of readily available information does not necessarily mean that the region is free of PFAS problems.

For more information about PFAS, see the websites of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, the EPA and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or contact your state or local public health department.

If you believe you have been exposed to PFAS and are concerned about your health, contact your health care provider. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have published guidance on PFAS exposure, testing, and clinical follow-up, including information to help health care professionals understand the monitoring and clinical implications of PFAS exposure.

This is an update to an article originally published on June 21, 2022.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by Kathryn Crawford, Middlebury

Read more:

Kathryn Crawford receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and the US Geological Survey.