Disfigured, weak, in fear of his life and desperate to return to Rome – Caravaggio in May 1610, raised a brush in his studio in Naples after months of recovery from a violent attack, to continue the work on which he painted The Martyr Saint Ursula.

In the autumn of the previous year, the artist’s various misdemeanors were volatile (including but not limited to: smashing a plate of artichokes into a waiter’s face; writing offensive poems; throwing stones at the police; killing someone terrible but dangerous -a bound pimp, for whom he fled with a death warrant on his head; an attack in Malta, for which he was imprisoned; and the subsequent daring escape from prison) that he was caught with, in the form of a vicious attack knife as he left a Neapolitan pub, in which his face was slashed several times.

His powerful friends in Rome, working to obtain a pardon for him, were concerned that he had been killed. He escaped, just, with his life, but Saint Ursula is his last painting.

The canvas, which has been in the Intesa Sanpaolo Collection since 1973, usually hangs in the bank’s huge gallery, the Gallerie d’Italia in Naples, a magnificent building from the Fascist period. It hangs almost alone and low on the wall, creating an uncomfortable feeling that the viewer is part of the terrible scene it depicts.

The painting is now traveling to Britain for the first time in nearly 20 years, to be exhibited at the National Gallery, in return for a short-term loan of two paintings by Velazquez. It will be hung alongside another late work by Caravaggio (real name Michelangelo Merisi, who spent much of his childhood in Caravaggio’s small town in Lombardy), the Nationalist’s own Salome The Head of John the Baptist, c 1609–10.

The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula is a rather unusual subject. The most common account of his story is that found in The Golden Legend, a collection of saints’ lives written in 1265 and widely circulated and read throughout Europe in the modern age.

A Christian princess of Britain or Great Britain, on the occasion of her betrothal to a Christian prince, Ursula asked for 10,000 (or 11,000, the calculation is less than exact) virgins (their purpose is not clear) and three years ” to commit her virginity”.

This was granted, and for this unmentioned parade they were sent on a ship to Rome, but when they returned through Cologne they were attacked by the Huns, who killed the women. The Prince of the Huns, however, took a fancy to the beautiful Ursula, and offered to marry her and spare her life. She refused, so he shot her with an arrow.

Caravaggio, a painter of extreme and intense violence even for the one who lived in violent times, is typical of many other painters who do not represent the 11,000 maids willingly killed by the troops, but in the intimate and terrible moment of Ursula. murder.

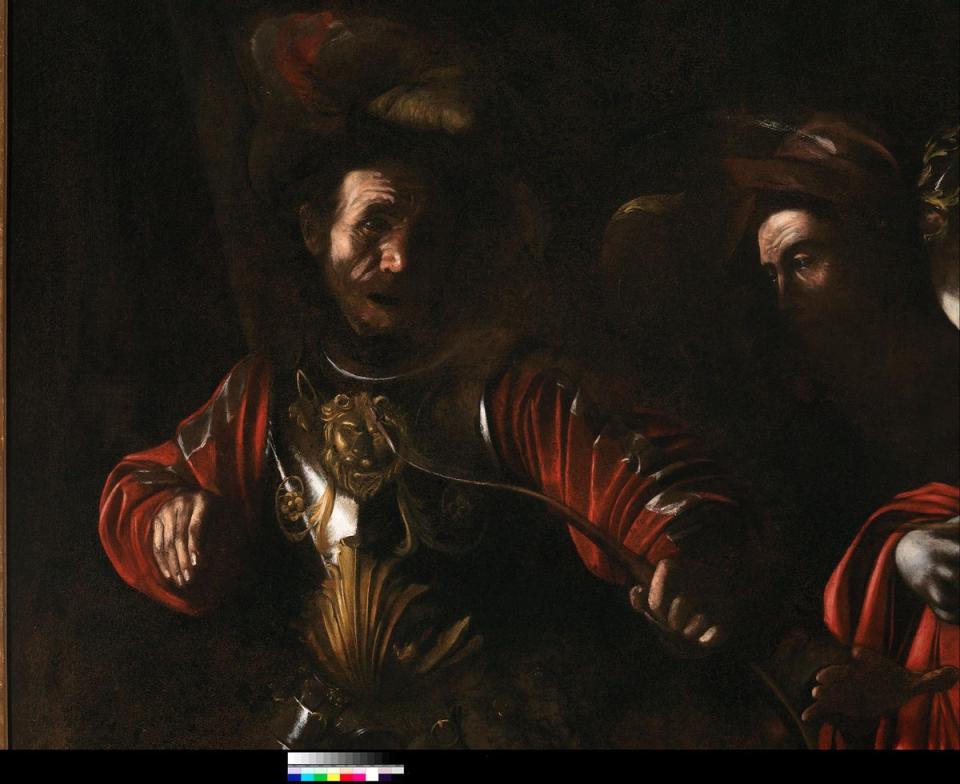

And it is extremely effective. The half-length, life-size figures are in the room with you. The painter’s signature interplay between light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, represents a terrible darkness against which the saint stands bare, and from which her murderers emerge.

She stands in the center-right in the tight composition, almost claustrophobic, closely surrounded by men, a bright glowing figure with a red blood wrap, with her hands clasped loosely around the shaft of the arrows that have just been fired into her body below her breast. , at point-blank range, at the tyrant’s left.

A moment of stillness, a slow-down, a freeze-frame of horror (Martin Scorsese, incidentally, is a fan, saying of Caravaggio’s works “You come to the scene halfway and you’re immersed in it.” I wonder if, with his ability to distill a story into an image, Caravaggio made a great filmmaker, although he was undoubtedly cancelled).

Before the painting, you almost want to go away. As exhibition curator Francesca Whitlum-Cooper says, “Even if you’re one of the Huns, there’s something about this that can’t be slammed.” One man in the scene, perhaps involuntarily, has thrown his hand out between the saint and the killer, as if to stop him. The murderer himself looks both mad and anguished, a glorious example of the painter’s ability to capture complex emotions in a split second.

Another soldier, in shining armour, stands to the right; his face is turned away from the audience but his position makes him look mute. And behind Ursula, with only her face visible, is another figure – Caravaggio himself, staring into space, haggard, pale and powerless.

There is, of course, a question, says Whitlum-Cooper, “how much you read to recover from a very serious attack on his late painting”.

“This is the last scene we have of a desperate man coming out of one of the most troubled times in his life,” she says. However, his familiar end, barely two months later, was not unexpected. Six weeks after the finished work was sent, Caravaggio himself was on his way to Rome, believing that a papal pardon had been granted.

His friends eagerly awaited his arrival – but at some point on the journey, whether due to a mistaken capture or some other altercation, he was separated from his belongings, and at Porto Ercole, according to his biographer Giovanni Pietro Bellori ( the subject of those scurrilous poems), he descended into a “malignant fever” and “died as miserably as he had lived”.

Yes he was a terrible and violent troublemaker, but my God he was a hell of a painter. The exhibition at the National will be small, but when was the last time you spent more than 30 seconds looking at a picture in an exhibition? Accompanying him, staring at him, close watching?

Caravaggio deserves this focus, and this rarely seen work. As Whitlum-Cooper says, “Our responsibility is to bring these amazing works of art to London, where people can see them for free.”

The paintings will be shown together with a couple of first edition biographies of the painter, and a rather boring letter – but one of enormous importance without which the exhibition would not take place at all.

Caravaggio painted Saint Ursula in Naples as a commission for the Genoese nobleman Marcantonio Doria. He was sent to Genoa and, says Nationalist director Gabriele Finaldi, “promptly disappeared”.

He went back to Naples in the 19th century with some unspecified Doria relatives, where he quietly hung out at his villa in Eboli for several years, until, probably due to debt or some other disaster, the family sold the property with all their contents. , to another noble family, the Romana-Avezzano (keep up), who later gave it to the bank in lieu of, yes, debt. Being an Italian aristo is not all glamour.

By then, no one was really sure what the scene represented, and certainly no one had a clue that it was Caravaggio – which is a shame for Romana-Avezzano, as the hunt would probably have been long settled. more effective. In any case, the bank accepted it as the work of the Calabrian painter Mattia Preti (1613-1699), who was greatly inspired by his extraordinary predecessor.

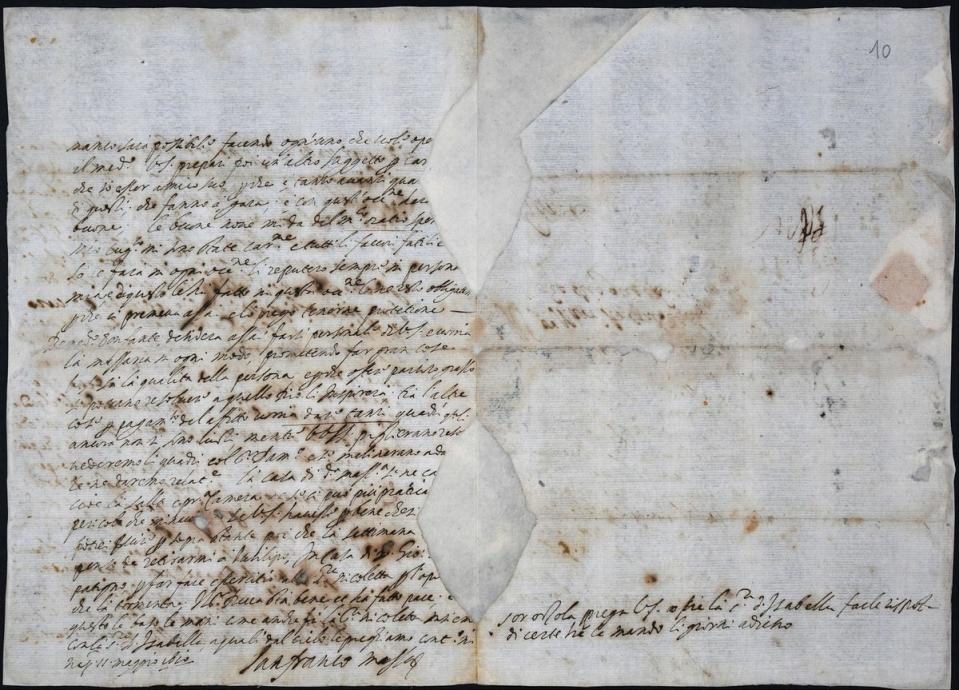

The letter was not to accept the key. In 1980 the art historian Vincenzo Pacelli found it in the state archives, and he finally understood what was in the picture. One Lanfranco Massa, in Naples, wrote the letter to his employer Marcantonio Doria in Genoa, regarding the painting he had commissioned from the most famous artist in the city – perhaps in Italy, at that time. It was businesslike, but apologetic:

“I had intended to send you the picture of St. Ursula this week, but to make sure it was perfectly dry I put it out in the sun yesterday, which, besides drying the varnish, softened it, Caravaggio performed it. rather thick; I will go to Caravaggio, he said, again to get his opinion on what to do so that I can be sure that it will not be destroyed; Signor Damiano saw it and was amazed, like everyone else who saw it.”

This connected the painting, the subject, and the history of the site, and two 17th century inscriptions on the back of the canvas confirmed the story. A new Caravaggio was discovered, just like that. Suffice it to say, the bank was much more diligent in preserving the much-needed image from that day on.

Ursula is still in what Whitlum-Cooper describes as a “slightly in danger” state. It has certainly darkened over time, and the varnish was further damaged on the painting’s journey back to Naples in 1832, when the packing materials stuck to its surface.

Imperfect historic restorations didn’t help, but conservation treatment in 2004 saw the hand stop for the first time in ages, finally revealing the full impact of the scene. And it’s a real heart stopper. Now London audiences can see it for the first time in a generation – in all its dramatic, terrifying glory. You have been warned.

The Last Caravaggio is at the National Gallery from 18 April to 21 July; nationalgallery.org.uk