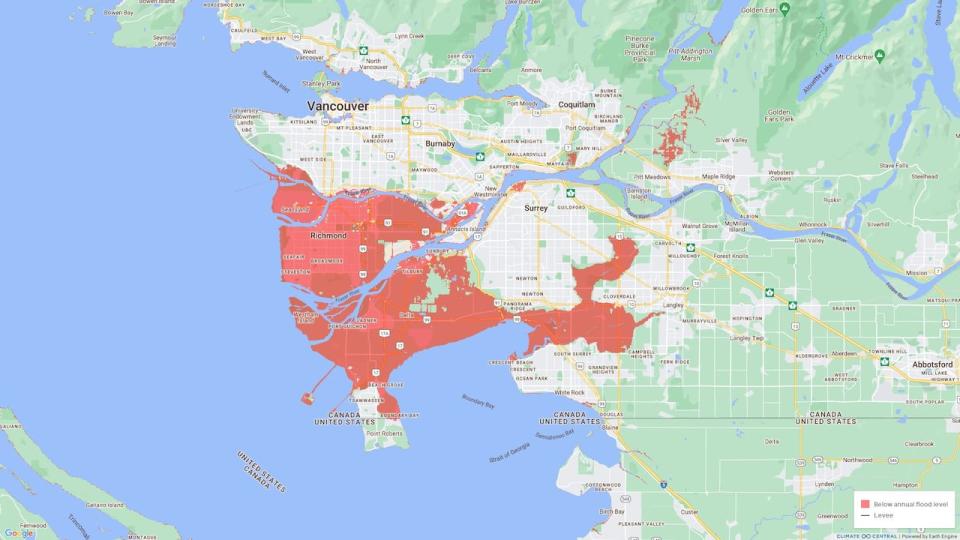

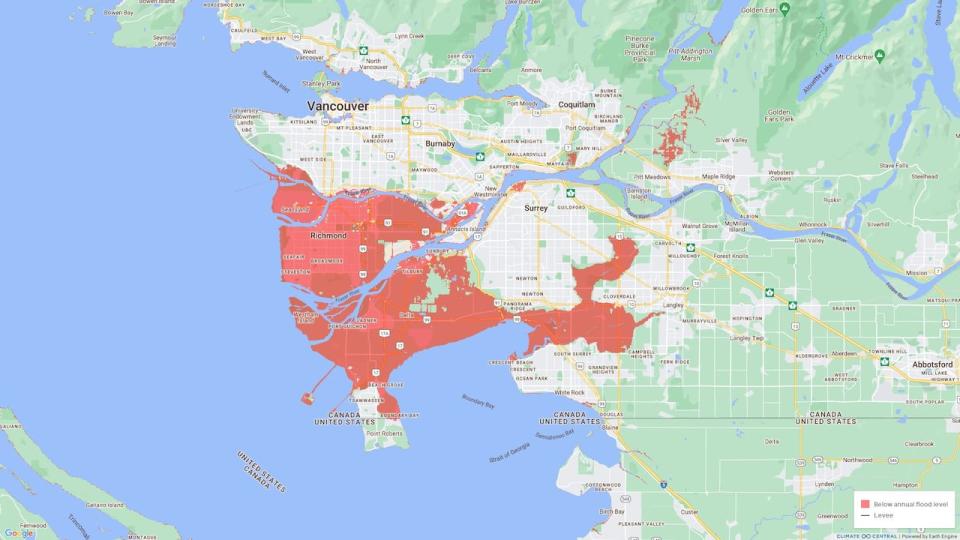

The new sea level data map shows that flood risk zones will extend higher and further inland on the Canadian coast, particularly affecting populated areas in parts of Metro Vancouver south of the Fraser River.

An estimated 325,000 people in Canada will live on land that falls in annual flood risk zones by 2100, according to information released Thursday by Climate Central, a non-profit scientists and communications group based in Princeton, New Jersey.

That’s a 10 percent increase on the group’s 2030 estimate of 295,000 people at risk of annual flooding.

The risk of coastal flooding is particularly significant in Richmond, Delta and South Surrey, said Peter Girard, Vice President of Climate Central.

By the end of the century, nearly all of Richmond including the airport, Delta and a large chunk of Surrey will be below annual flood levels, the new map projects.

A new map from US-based research group Climate Central shows that flood risk zones will expand further inland in parts of Metro Vancouver in the future. (Submitted by Climate Central)

“This is not surprising,” Girard said during a zoom interview with CBC News.

“As you look south of Vancouver, you see areas that are already at risk of coastal flooding … and those risks increase over time and by the end of the century you’re going to see significant risks.”

Previous estimates from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change will increase sea levels by 0.5 meters by 2050 and one meter by 2021 along the BC coast, mainly affecting areas in the Lower Mainland such as Richmond and the Delta.

It’s time to prepare for the risks, Girard said.

“If you can look 30 or 60 years into the future … planners in those areas can start preparing for the risk before it happens,” he said.

Municipalities south of the Fraser River have known the challenge ahead for a long time, said Delta Mayor George Harvie.

“We are repairing [dikes] and looking at areas that are subject to wind and storm surge and protecting our residential areas,” Harvie told CBC News.

But the Delta mayor said the responsibility for maintaining dikes falls heavily on local governments.

Flooding in Sumas Prairie, Abbotsford, BC. The pond breach in Abbotsford, BC contributed to catastrophic flooding across the Sumas plains in 2021. (Oliver Walters/CBC)

“We have about 67 kilometers of dikes in Delta and we can bring them up to standard [can cost] $2 billion and that’s just for Delta. It’s not going to happen.”

In 2011, the BC government transferred responsibility for operating and maintaining dikes to local government.

Harvie said he would like to see the province get more involved.

Climate experts say dikes are not a silver bullet, and point to other defenses municipalities can use.

According to Karen Kohfeld, director of SFU’s School of Environmental Science, one such measure includes wetland restoration.

“It’s a classic example of some of the nature-based solutions that can be implemented to help protect the coast on a larger scale,” she said.

The SFU professor said wetlands and marshes act as a protective system to reduce coastal energy by lowering the amplitude and speed of ocean waves, which mitigates storm damage and shields shorelines from erosion.

Mayor Delta Harvie said the city is partnering with the City of Surrey and Semiahmoo First Nation in a similar marshland restoration project called the Living Dike Pilot Project.

With the project at Boundary Bay, the largest salt marsh in southwestern Canada, collaborators aim to gradually add sediment to the marsh over a 30-year period. The plan aims to increase the height of the marsh, creating a natural barrier that can withstand sea level rise.

What causes sea levels to rise?

Kohfeld said global warming is one of the biggest contributors to sea level rise.

The ocean is getting warmer, she explained.

“It’s storing heat, and as the water rises, it expands. And it’s that simple expansion of seawater that causes the volume of the sea to increase.”

In addition, melting glaciers – large sheets of ice and snow – are adding more water to the Earth’s oceans, she said.

Although it may not be hit by a 50 centimeter or one meter rise in sea levels over the next 75-odd years, experts warn against “underestimating the power of water”.

Kohfeld said the increase in water volume will increase the impact of king tides and storms.

Girard Climate Central said rising global emissions contribute to elevated coastal flooding risks.

“As long as we pollute, as long as carbon dioxide continues to enter our atmosphere, these impacts will become more severe,” he said.