Flow, or being “in the zone,” is a state of heightened creativity, enhanced productivity and blissful consciousness, which some psychologists believe is also the secret to happiness. This is considered the brain’s fast track to success in business, the arts or any other field.

But to achieve flow, one must first develop a strong foundation of expertise in their craft. That’s according to a new neuroimaging study from Drexel University’s Creativity Research Lab, which recruited jazz guitarists in the Philly area to better understand the key brain processes underlying flow. Once expertise has been achieved, the study found, this knowledge must be released and not over-thought to achieve the flow.

As a cognitive neuroscientist who is the senior author of this study, and a university writing instructor, we are a husband and wife team who collaborated on a book about the science of creative insight. We believe this new neuroscience research points to practical strategies for improving and clarifying innovative thinking.

Jazz musicians flow

The concept of flow has fascinated creative people since pioneering psychological scientist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi began investigating the phenomenon in the 1970s.

However, half a century of behavioral research has not answered many fundamental questions about the brain mechanisms of flow-dependent attention.

The Drexel experiment pitted two opposing theories about flow against each other to see which better describes what happens in people’s brains when they generate ideas. One theory suggests that flow is a state of intense focus on a task. The other theory hypothesizes that flow involves relaxing one’s focus or conscious control.

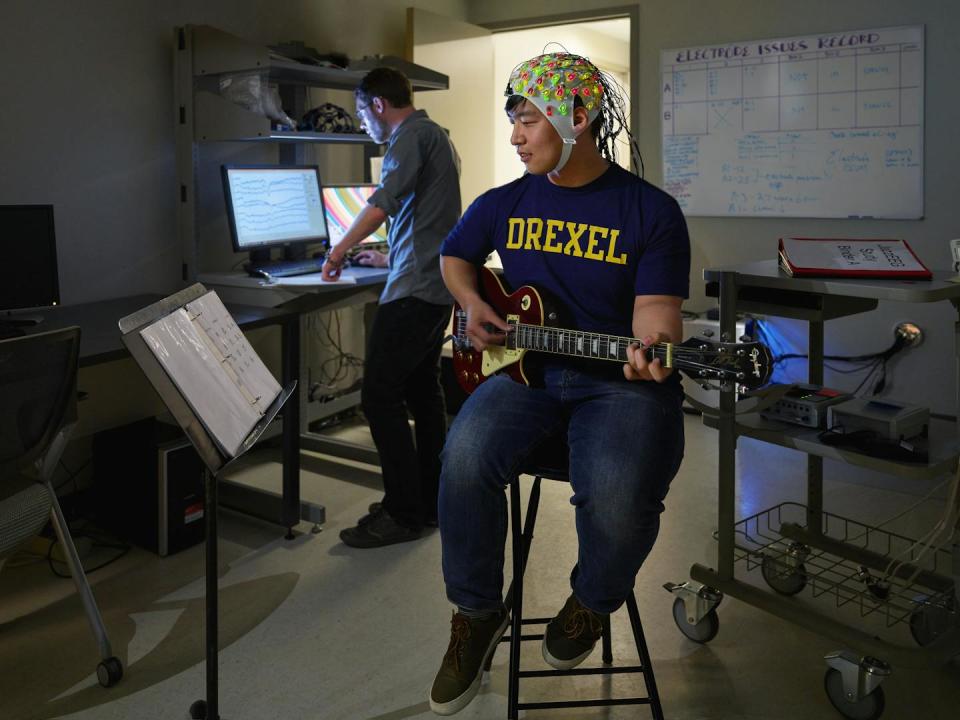

The team recruited 32 jazz guitarists from the Philadelphia area. Their level of experience ranged from novice to veteran, quantified by the number of public performances they gave. The researchers put electrode caps on their heads to record their EEG brain waves as they sequenced chords and rhythms provided to them.

Jazz improvisation is a favorite vehicle for cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists studying creativity because it is a measurable real-world task that allows for divergent thinking—the generation of multiple ideas over time.

The musicians themselves rated the amount of flow they experienced during each performance, and those recordings were later played to expert judges who rated them for creativity.

Train hard, then surrender

As jazz great Charlie Parker is said to have suggested, “You have to learn your instrument, then you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up on the bandstand, forget all that and cry.”

This sentiment is consistent with the results of the Drexel study. The performances that the musicians rated themselves highly were also considered by the external experts to be more creative. Furthermore, the most experienced musicians rated themselves as flowing more than the novices, suggesting that experience is a prerequisite for flow. Their brain activity showed why.

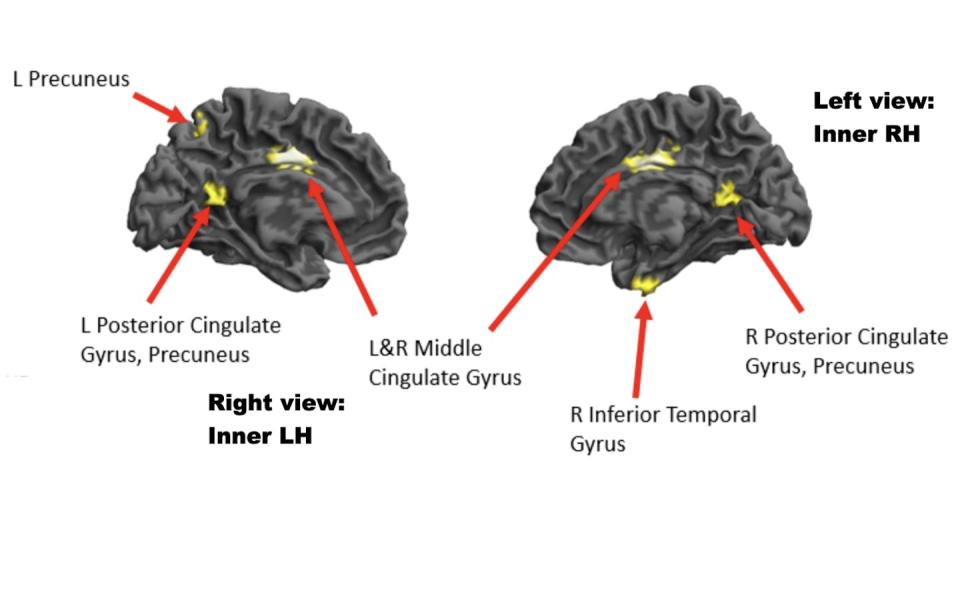

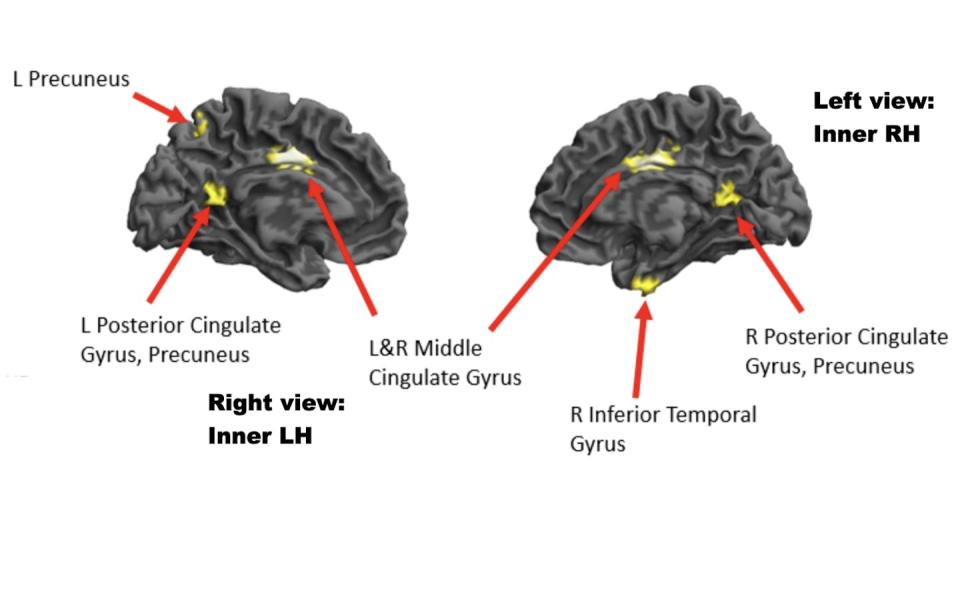

The musicians who experienced flow while performing showed reduced activity in parts of their frontal lobes known to be involved in executive function or cognitive control. In other words, flow was associated with easing conscious control or supervision of other parts of the brain.

And when the most experienced musicians performed in a flow state, their brains showed greater activity in areas known to be associated with hearing and vision, meaning they were improvising and reading chord progressions and listening to the rhythms provided. .

In contrast, the less experienced musicians showed little flow-related brain activity.

Creativity flow vs nonflow

We were surprised to learn that flow-state creativity is very different from nonflow creativity.

Previous neuroimaging studies have suggested that thoughts are normally produced by the default mode network, a group of brain areas involved in introspection, daydreaming and imagining the future. The default mode network spins ideas like an unattended garden hose spouting water, without guidance. The aim is provided by the executive control network, which resides mainly in the frontal lobe of the brain, which acts like a gardener that directs the hose to direct the water when it is needed.

Creative flow is different: no hose, no gardener. The default mode and executive control networks are disrupted so that they cannot interfere with the specific brain network that highly experienced people have built to produce ideas in their area of expertise.

For example, familiar but relatively inexperienced computer programmers may have to work their way through each line of code. Old coders, however, tapping into their specialized brain network for programming, may just start writing code fluently without overthinking it until they complete – perhaps in one sitting – a first draft program .

Coaching can be a help or a hindrance

A 2019 study from the Creativity Research Laboratory supports the findings that expertise and the ability to relinquish cognitive control are critical to achieving flow. For that study, musicians were asked to play “more creative” jazz. With that direction in mind, the non-expert musicians were indeed able to improvise in a more creative way. This seems to be because their improvisation was largely under conscious control and could therefore be adjusted to meet demand. For example, during a debriefing, one of the novice performers said, “I wouldn’t use these techniques intellectually, so I had to actively choose to play more creatively.”

On the other hand, the expert musicians, whose creative process had been instilled by many years of experience, were unable to perform more creatively when asked to do so. As one of the experts said, “I felt boxed in, and it was an obstacle to think more creatively.”

The takeaway for musicians, writers, designers, inventors and other creative people who want to take advantage of the flow is that training should involve intense practice and learn to step back and let one’s skill accept. Future research may develop possible means of releasing control once sufficient expertise has been achieved.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: John Kounios, Drexel University and Yvette Kounios, Extended University

Read more:

John Kounios currently receives grant funding from DiagnaMed Inc. for research on brain aging and in the past has received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation for cognitive neuroscience research on memory, problem solving and creativity.

Yvette Kounios does not work for, consult with, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and does not she disclosed any relevant connections beyond their academic appointment.