When I was seven years old, I started noticing small white patches on my body and by the time I reached 11 they had spread all over the world. They were symmetrical, the same on all sides.

I later found out I had vitiligo, a rare autoimmune skin condition characterized by the development of these light patches on the skin. They occur due to the loss of melanin, the cells responsible for skin color. Although vitiligo can affect any part of the body, for most people including me, it appears on the face, neck, hands, arms and legs.

The condition makes the affected areas sensitive to sunlight, so it required me to take Vitamin B shots, supplements, folic acid and have my thyroid checked every year. It affects around one per cent of the world’s population and one in 100 people in the UK.

Over the past decade, more people with vitiligo have gained prominence in the public eye. In particular, models Amy Deanna, the first model with vitiligo to appear at CoverGirl cosmetics, and Winnie Harlow, the first model with the condition to walk for Victoria’s Secret. The Canadian native first gained attention when she opened up about her condition in an Instagram post in 2014 and has remained tight-lipped about it.

In one powerful post she wrote, “My skin has changed so much in the last 6 years.. it’s unbelievable. The evolution of Vitiligo is beautiful. Don’t be ashamed of what makes you different. My skin changes all the time, I relearn how to do my makeup all the time based on what suits it at that time. Skin is just skin. We should not judge based on him, condition or race. Like our mind and soul, my skin is constantly changing.” [sic]

It is not known for sure what causes vitiligo, but research suggests that it may be genetic. In my case, it didn’t reach a generation, although I have second and third cousins with vitiligo. There is no permanent cure, although there are treatments such as topical steroids or phototherapy available that may slow the progression of vitiligo or allow melanocytes to return.

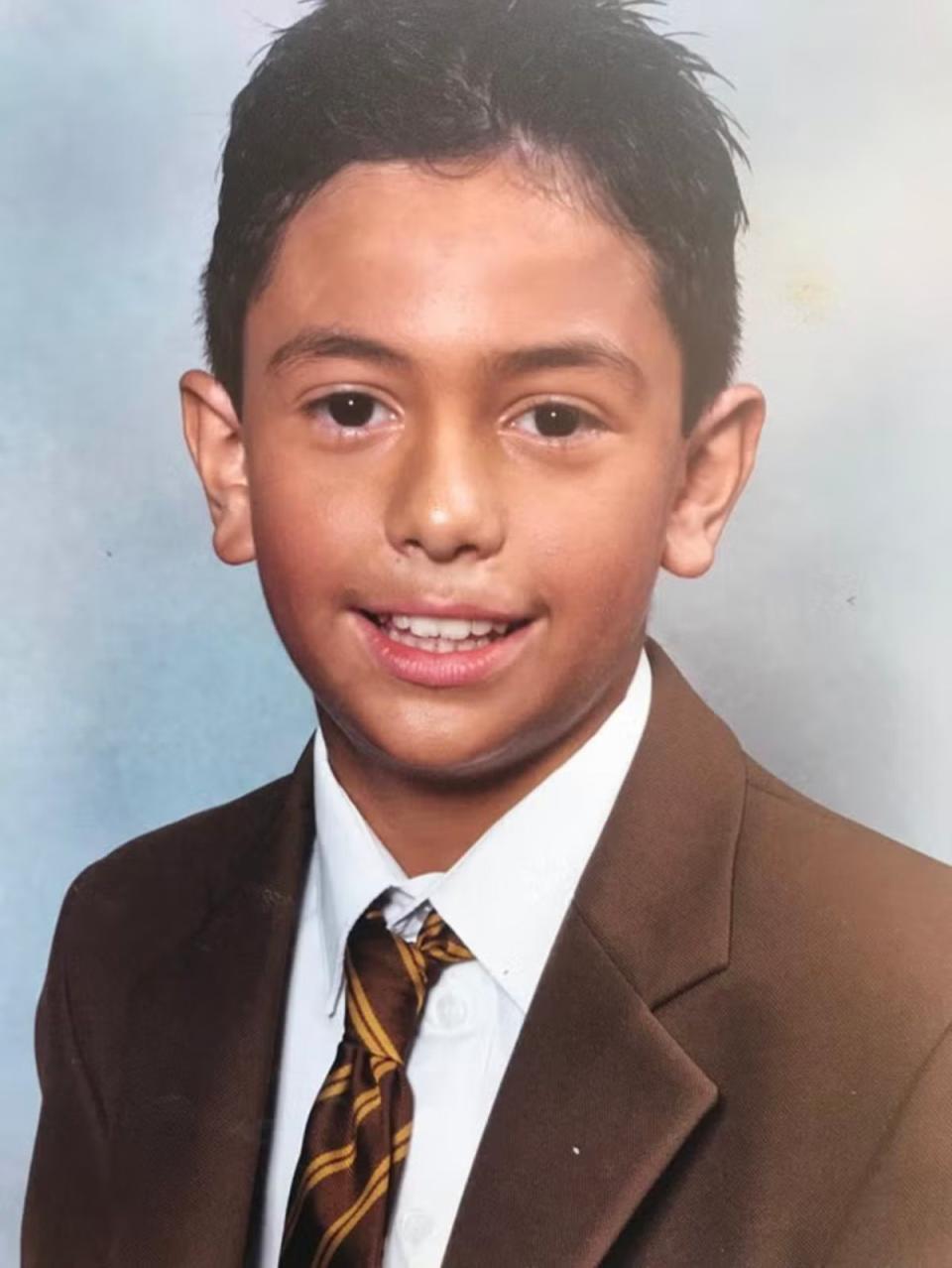

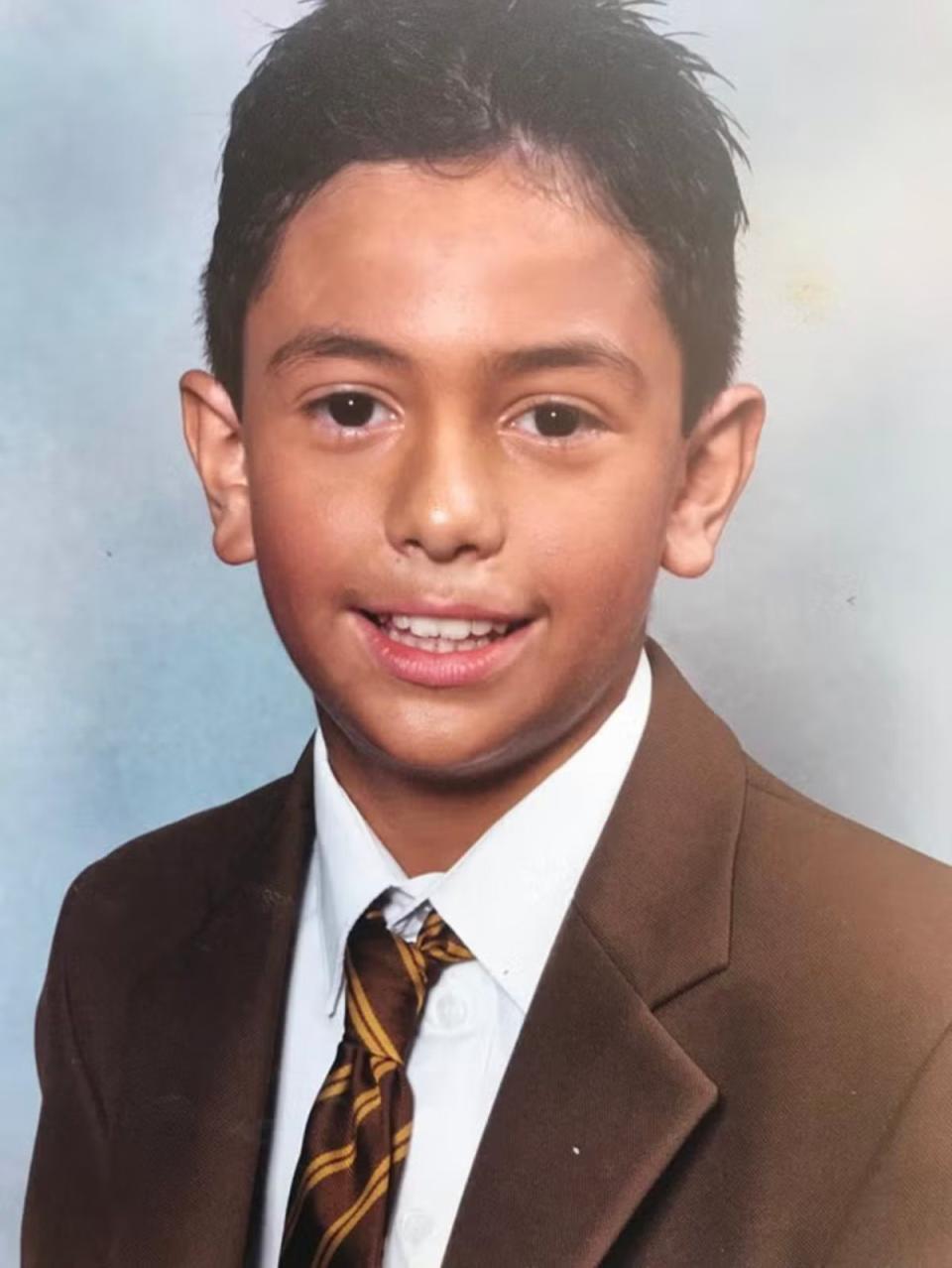

During my childhood I used makeup to cover my vitiligo. Although it didn’t stop me from doing anything at school, I was always conscious of touching my face during sports activities. I was confident, I wasn’t bullied or bullied, but I struggled with a deep inner conflict that didn’t allow me to accept the flawless look.

At school, I was confident, I was never bullied or bullied, but I faced a deep inner conflict that did not allow me to accept the flawless sight.

I grew up in a Turkish-Cypriot family and my parents knew very little about the condition. They were very insular, and stuck in their own cultural circles. Rather than treating Vitiligo as a medical condition, they approached it as a cosmetic issue. I felt anxious about opening up to them, because I was feeling that it was an issue that needed to be hidden.

I believed that applying makeup on my face every day as a normal child was the right way to handle it. My mother tried different treatments to help. From drinking me tree root concoctions to using various topical steroids. Although none of these treatments really had any effect. At the age of 14, she used an ointment recommended by a Turkish doctor, which contained acid in our shock. I reacted badly and ended up in A&E.

Until eight years ago, as an adult, my regime of wearing makeup remained daily; I would wake up in the morning, take a shower and then apply it before I went to work. However, in 2016, just weeks before I married my wife Amy, I stopped wearing it. The ceremony was to be held in Jamaica, where Amy and I were when I was 21 years old. I remembered that I really struggled to keep my makeup on in the heat.

So when we decided to get married there, and I remembered the experience of being hot and uncomfortable, I understood; I didn’t need this for my wedding day. However, I was conflicted. I went through an internal emotional battle about whether to wear makeup on that special day or be brave in showing my authentic self. For years I believed that if I didn’t wear makeup then I wouldn’t feel my best, attractive or beautiful. This was the reason I continued to cover up my vitiligo until I met Amy.

I think she saved me in a way. She inspired a sense of self in me that my parents, loving as they were, never had – giving me the certainty that vitiligo does not diminish my beauty.

Vitiligo was perceived differently 20 years ago, and although it is now an accepted aspect, I believe it is still underrepresented. Not just with vitiligo but with all skin disorders, in the celebrity landscape and in wider society.

Through an initiative in my workplace called London Voices, I am raising awareness, and the response has been overwhelming. I believe that everyone has their own insecurities and mine is vitiligo, but I want people to understand that it helps to talk about it.

I am the parent of two boys who I know will be curious about my skin. I want to be able to share my experience with them and help them understand that there is nothing bad.