Unlike most country histories, the ‘Archaeological Atlas of France’ does not include Kings, Presidents, revolutions or major battles.

Instead, it describes thousands of years of human occupation, including huge changes in France’s borders, its climate, its population and the way of life of its inhabitants.

100 new maps have been created from the results of thousands of excavations over the past twenty years.

What was found in the soil gave clues to human societies that buried things themselves, for example in tombs, or simply over time.

Published by Inrapthe National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research, in November, the Atlas sold out and was recently reissued.

“Often, what reaches the general public is what is visible and preserved. We want to show the invisible heritage under our feet,” explained Inrap President, Dominique Garcia.

The maps show information but “white areas” for “questions” he said.

Origin story

The Atlas begins with a map of Africa followed by Homo Sapiens entering what is now France, looking for their first works of art. It ends with the Second World War and a passage through colonial France and abroad.

One part of the Atlas focuses on the archeology of Guyana (1795-1953) studying the history of slavery, as a penal colony and as a gold pan.

Garcia explained that the authors wanted to “show the space abroad for its own history, and not only from the moment France set foot there”.

The soil archives

Each map represents a layer of French history and is accompanied by summaries, photographs, plans and artists’ impressions to depict landscapes that have long since disappeared.

It is divided into periods and major themes looking at the agricultural, artisanal, funerary and commercial practices that the soil archives reveal.

The Atlas also shows how socio-economic and cultural processes fit together, whether through carved stones, statues, ceramics and necropolises, or once living elements, such as skeletons or depleted remains such as fauna and seeds.

Among the topics are the spread of valuable objects in the Neolithic period, such as alpine jade axes found as far as the top of Brittany, changes in cremation practices in the Bronze Age, or the spread of the plague between 1347 and 1351, which is amazing. reminiscent of the Covid-19 pandemic map.

It also looks at contemporary issues, from epidemic management, climate change and urban development.

The History of Archaeological Maps

The Commission de Topographie des Gaules (CTG) made the first attempt at archaeological cartography on this scale between 1858 and 1879.

In 1858, the CTG aimed to produce three maps of Gaul, one from the Celtic period before the Roman conquest; the second, from the Gallo-Roman period; and the third, during the Merovingian period.

The project did not turn out as originally planned. Although all the maps were completed, only one part of the ‘Dictionnaire archéologique de la Gaule – Époque Celtique’ was published between 1875 and 1878.

A 2001 law aimed at preserving underground heritage through excavations before work began to develop the land accelerated the mapping process.

The French Archaeological Atlas synthesizes excavation data from as far back as the 19th century.

A story of wine in Gaul

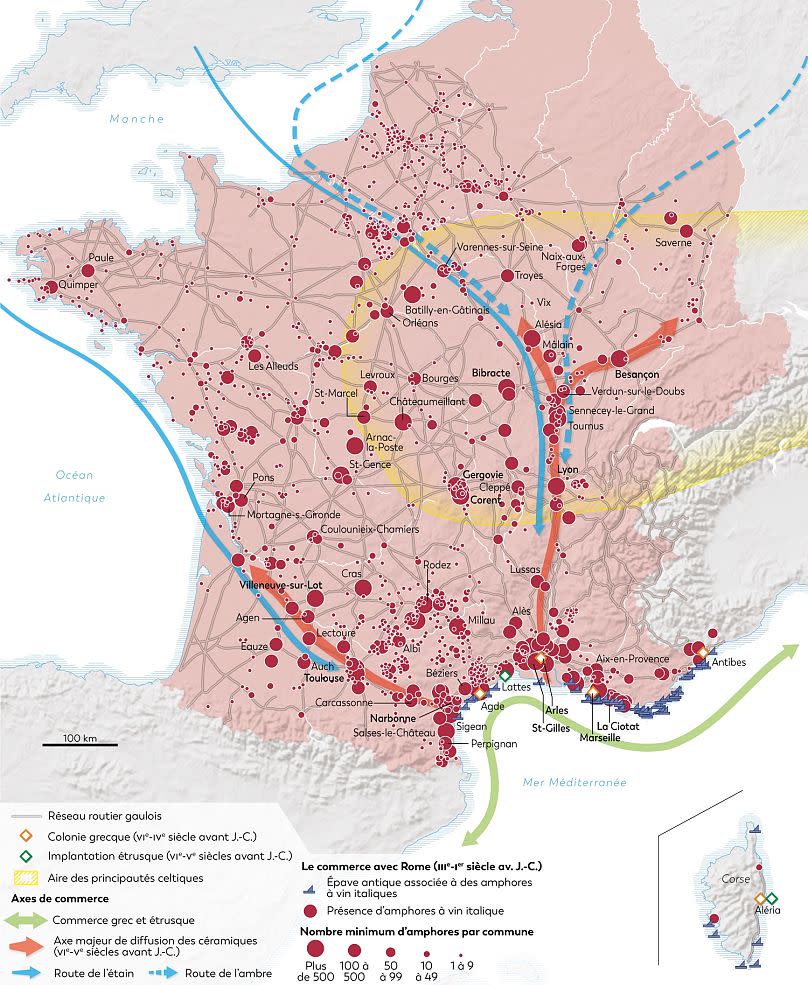

Mediterranean and Gallic wine map it shows how the territory of the Gauls attracted the tin and amber merchants from the Mediterranean, Greece, Etruria, Phoenicians and Rome, who established trading posts and colonies from the end of the seventh century BCE.

On the south coast of Gaul many high-value manufactured products, such as Attic ceramics, ornaments and Greek wine amphorae, have been found since the end of the First Iron Age. This suggests a boom in exchanges between indigenous populations and Mediterranean traders.

After the Roman conquest of Carthage at the end of the Second Iron Age, the Romans developed their commercial network in the western Mediterranean and further north.

In Gaul, they found raw materials (metals and salt), slaves, and raw or processed agricultural products that they exchanged for wine that came mainly from the Tyrrhenian coast (Etruria, Lazio, Campania) and some tableware.

Wine amphoras were transported from the Mediterranean ports of Gaul to their northern territories via the rivers Garonne, Rhône and Saône.

In the second half of the third century BCE came a warmer and drier climate known as the “better Roman climate”. This enabled an increase in agricultural production in non-Mediterranean Gaul.

Large rural estates, owned by the minority of the Gauls, had surpluses, which could be exchanged for imported products, especially wine, an important part of feasts, large community gatherings and certain religious ceremonies.

Wine was previously cultivated only in the Gallic territory of Marseille before the Roman Conquest.