Scientists hoping to find life in the liquid water oceans beneath the frigid, icy shell of Jupiter’s moon Europa may get a helping hand from a “cosmic snowball fight” that once took place on this planet.

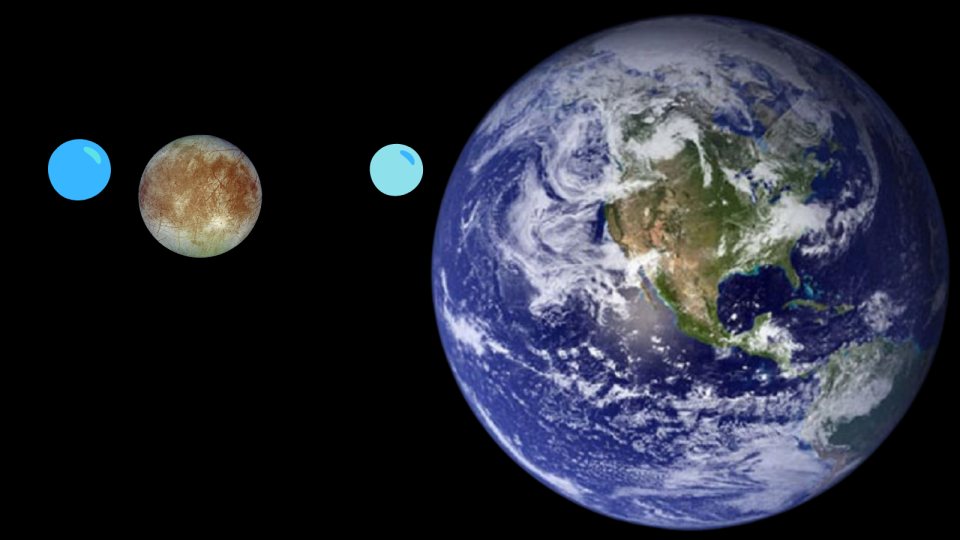

Europa has long been seen as a prime location for the solar system to look for evidence of simple life — life as we know it, at least). That’s because this Jovian moon, which is 1,940 miles (3,100-kilometers) wide, is believed to host saltwater oceans two to three times the volume of all the oceans on Earth combined. These oceans are believed to lie beneath the icy crust of Europe, and such aquatic environments are key regions for the emergence of life. However, the likelihood that Europa will host life, and the shape that life may take on this world, depends greatly on the thickness of this moon’s ice shell. That thickness is something that scientists have so far struggled to determine.

But now, a team of planetary scientists may have some clues about the final value. After observing large craters on Europa caused by asteroids and comets that hit the moon, the researchers used these observations to determine that Enceladus’ shell is about 12 miles (20 kilometers) thick. And this shell, they say, probably floats on an ocean 40 to 100 miles (60 to 150 kilometers) deep around the moon’s rocky core.

Related: Jupiter’s ocean moon Europa may have less oxygen than we thought

“Understanding the thickness of the ice is critical to theorizing about possible life on Europa,” Brandon Johnson, co-team leader and associate professor at Purdue University’s College of Science, said in a statement. “How thick the ice shell is, controls the type of processes that are happening within it, and that’s really important for understanding the exchange of material between the surface and the ocean.

“That’s what’s going to help us understand how all kinds of processes happen on Europa,” Johnson continued, “and it’s going to help us understand the possibility of life.”

Digging into an icy shell

Life as we know it needs three main components: Liquid water, certain chemical elements such as carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulphur, and a source of energy.

Scientists believe that life on Europa would likely be powered by chemical reactions alone, however, instead of photosynthesis we see Earth-based plants and simple Earth-based life forms involved.

This is because Europa is constantly being blasted by radiation from Jupiter, meaning that life would not be able to exist on its surface. That means that any life in Europe would have to live under the ice, where there is no sunlight. And sunlight is needed for photosynthesis. So for photosynthesis to work in this situation, the ice layer would have to be thick enough to protect simple life forms like microbes from the radiation but still thin enough to allow this radiation to provide simple life with energy.

Specifically, the team estimated the thickness of Europa’s ice shell by examining observations made by the Galileo spacecraft in 1998. The scientists then modeled a crater using a combination of physical characteristics and surface qualities that the divers could to create.

Johnson is well versed in studying massive collisions that planets may have had during the solar system’s 4.5 billion year history, and how these impacts shaped life.

“Effect cratering is the most ubiquitous surface process for shaping planetary bodies,” he said. “Craters can be found on almost every solid body we’ve ever seen. They’re a major driver of changes in planetary bodies. When an impact crater forms, it’s essentially probing the subsurface structure of the planetary body.

“By understanding the sizes and shapes of the craters on Europa and reproducing their formation with numerical simulations,” he continued, “we are able to get information about how thick its ice shell is.”

This study of a creature may tell researchers a lot about Europa’s icy shell, and even a little about the ocean beneath it as well as how material is exchanged between the two layers.

Related Stories:

— In their search for alien life, scientists are searching for extrasolar Earth-Jupiter duos

— Watch this Jupiter moon lander handle harsh terrain it may face on Europa (video)

– NASA’s Juno probe sees active volcanic eruptions on volcanic moon Io (images)

“Previous estimates showed a very thin layer of ice over a thick ocean. But our research showed that there must be a thick layer – so thick that convection in the ice is likely, which has been debated before,” Shigeru Wakita, a team of co . – leader and researcher at the Purdue University College of Science, said in the statement.

What this study reveals about the rocky core of this Jovian moon is less clear, and the interaction between the rocky core and the water may be necessary to find out what minerals are in the oceans Europe. So there is still a long way to go before scientists can even confirm the possible emergence of life on this moon of Jupiter.

The team’s research was published on Wednesday (March 20) in the journal Science Advances.