A German man has probably been cured of HIV, a medical milestone achieved by six others in the more than 40 years since the AIDS epidemic began.

The German, who prefers to remain anonymous, was treated for acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, with a stem cell transplant in October 2015. He stopped taking his antiretroviral drugs in September 2018 and remains in viral remission without no rebound. Multiple ultra-sensitive tests found no viable HIV in his body.

In a statement, the man said of his remission: “A healthy person has many wishes, one sick person.”

It is expected that the case, which investigators said provides vital lessons for HIV cure research, will be presented on Wednesday by Dr. Christian Gaebler, a medical scientist at the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, at the 25th International AIDS Conference in Munich.

“The longer we see these HIV remissions without any HIV therapy, the more confident we’ll be that we’re likely to see a situation where we’re actually capable of eradicating all HIV,” Gaebler said.

As with all previous cases of a potential HIV cure, experts are keen to temper the public’s excitement with a caveat: The treatment that blocked the virus in the seven patients will only ever be available to a select few. Each contracted HIV and later developed blood cancer, which required stem cell transplants to treat the malignancy.

The transplants – in most cases from donors chosen for their immune cells, the cells that HIV targets – had a rare natural resistance to the virus and were crucial to eradicating all viable or competent copies of the virus from the body

Stem cell transplants are highly toxic and can be fatal. It would therefore be unethical to provide them to people with HIV only to treat specific diseases, such as blood cancer.

HIV is very difficult to cure because some of the cells it infects are long-lived immune cells that are in a dormant state or go into a dormant state. Standard antiretroviral treatment for HIV only works on immune cells which, typical of infected cells, are actively making new viral copies. Therefore, HIV remains within resting cells under the radar. Collectively, such cells are known as the viral reservoir.

At any time, a reservoir cell can start producing HIV. This is why if people with the virus stop taking their antiretrovirals, their viral loads usually disappear within weeks.

Stem cell transplants have the potential to cure HIV in part because replacing a cancer-stricken person’s immune system with the donor’s healthy immune system requires chemotherapy and sometimes radiation.

In five of the seven cases of a definite or possible HIV cure, doctors found donors with rare natural defects in both copies of a gene that results in a specific protein, called CCR5, on the surface of immune cells. Most types of HIV use that protein to infect cells. Without functional CCR5 proteins, immune cells are resistant to HIV.

A German donor had only one copy of the CCR5 gene, which means his immune cells probably have about half the normal amount of that protein.. Furthermore, he only had one copy of the gene himself. Together, those two genetic factors could increase his chances of a cure, Gaebler said.

Although two copies of the defective CCR5 gene are rare, occurring in about 1% of people with native northern European ancestry, one copy occurs in about 16% of those people.

“So the study suggests that we can expand the donor pool for these types of cases,” said Dr. Sharon Lewin, director of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia, in a media briefing. last week.

Interestingly, a man treated in Geneva whose potential HIV cure was announced last year had a donor with two normal copies of the CCR5 gene. So his transplanted immune cells were not HIV resistant.

These two recent European cases raise critical questions about the factors that contribute to a successful HIV cure.

“The level of protection one might expect from a transplant should not be enough to prevent the virus from surviving and spreading,” said Dr. Steven Deeks, a leading HIV cure researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who is not related. . care of the German man, who was told about his situation. “There are a lot of testing theories, so I’m hopeful that we’ll learn something here that could shape the next generation of medicine studies.”

Gaebler said that having immune cells resistant to HIV in the mix definitely improves the chance of curing the virus with a stem cell transplant. And yet, he said, missing that safety net, or one with several holes in it, as in the case of the German man, does not prevent success.

“We need to understand how the new immune system was able to graft into his body and how it was able to eliminate HIV reservoirs over time,” he said. Suggesting that the transplanted immune cells may have attacked the viral reservoir, he said, “The donor’s innate immune system may play an important role here.”

The other 6 have either cured or may be cured of HIV

Each initially had a pseudonym based on where they were treated.

-

Adam Castillejo, as the “London patient.” Castillejo, 44, a Venezuelan man living in England, received a stem cell transplant for AML in 2016 and stopped HIV treatment in 2017. He is considered cured.

-

Marc Franke, the “Düsseldorf patient.” Treated with a stem cell transplant for AML in 2013, Franke, 55, went off antiretrovirals in November 2018 and is considered cured.

-

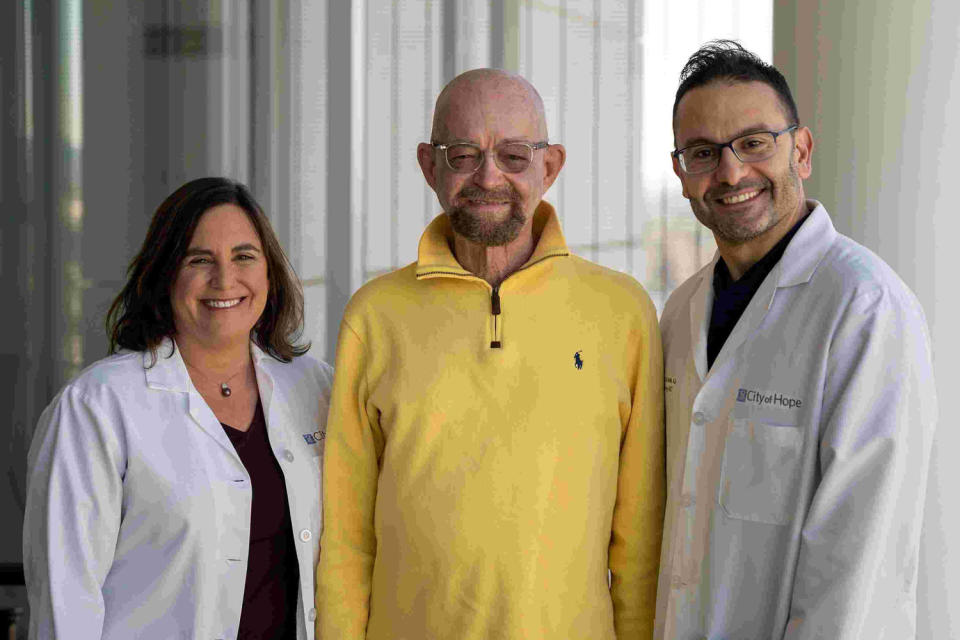

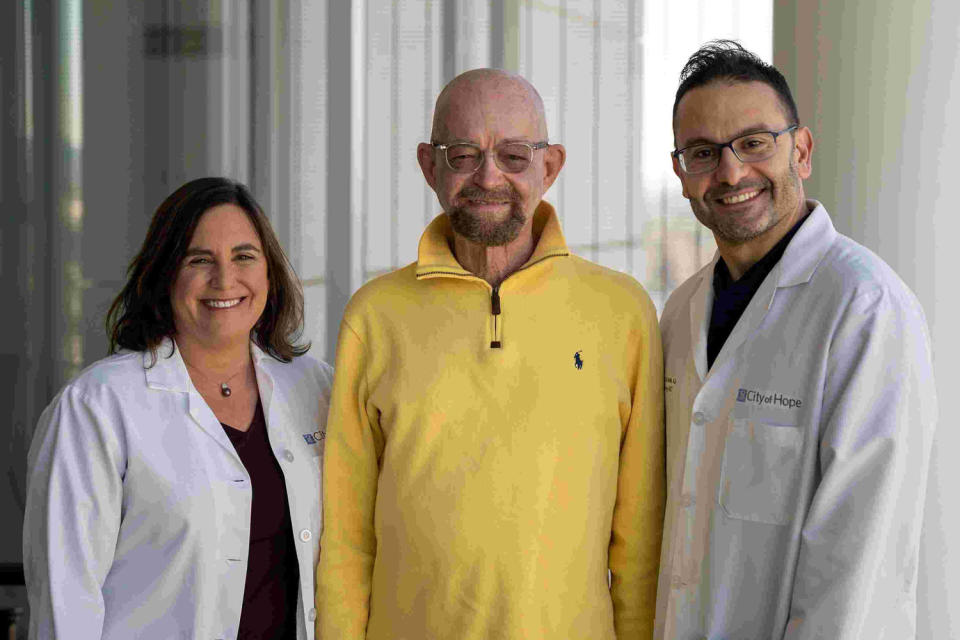

Paul Edmonds, as the patient “City of Hope.” Edmonds, the oldest possible cure case at 63 when he received a stem cell transplant for AML in 2019, received chemotherapy at a reduced intensity because of his age. Off antiretrovirals from March 2021, it will be considered cured when it hits five years without any viral rebound. In an interview, he expressed excitement about a new case of possibly curing a man, too, and said, “My vision is clear: a world where HIV is no longer a sentence, but a footnote in history.”

-

The “New York Patient.” The first woman and person of mixed race ancestry to possibly be cured, she was diagnosed with leukemia in 2017 and received a stem cell transplant augmented with umbilical cord blood, which allowed for a lower genetic match with her donor, expanding the donor pool. .

-

The “patient in Geneva.” In his 50s, he was diagnosed with a rare blood cancer in 2018 and has been off HIV treatment since November 2021. Researchers remain cautious about his cure status because his immune cells are not resistant to HIV.

Franke, Edmonds and Castillejo, who are now friends, are expected to attend the HIV conference in Munich.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com