Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

Science is revolutionizing our understanding of the past.

Paleogenetics solves amazing secrets from DNA hidden in bones and dirt. Artificial intelligence decodes ancient texts written in forgotten scripts. Chemical analysis of molecular residues left on teeth, cooking pots, incense burners and building materials reveals details of past diets, smells and building techniques.

These are the six mysteries about human history that scientists have cracked in 2023. Plus, one that researchers are still scratching their heads.

The true identity of a prehistoric leader

Buried with a stunning crystal dagger and other priceless artefacts, the 5,000-year-old skeleton discovered in 2008 in a tomb near Seville, Spain, clearly once belonged to an important person.

The individual was originally thought to be a young man, based on analysis of the pelvis bone, in the traditional way scientists determine the sex of human skeletal remains.

However, analysis of tooth enamel, which contains a type of protein with a sex-specific peptide called amelogenin, determined that the remains were female rather than male.

In other studies, the technique also eliminated the “man the hunter” cliché that informed much thinking about early humans.

“We think this technique will open a whole new era in the analysis of the social organization of prehistoric societies,” Leonardo García Sanjuán, a professor of prehistory at the University of Seville, told CNN in July when it was discovered. public.

The ingredient behind the legendary strength of Roman concrete

Roman concrete is proven to last longer than its modern equivalent, which can deteriorate within years. Take, for example, the Pantheon in Rome, which has the largest unreinforced dome in the world.

The scientists behind a study published in January said they had discovered the mystery ingredient that allowed the Romans to make their building materials so durable and build elaborate structures in challenging places such as docks, sewers and earthquake zones. land.

The study team analyzed 2,000-year-old concrete samples taken from a city wall at the Privernum archaeological site in central Italy that are similar in composition to other concrete found throughout the Roman Empire.

They found that white chunks in the concrete, called lime clasts, gave the concrete the ability to heal cracks that developed over time. The white lumps were previously ignored as evidence of sloppy mixing or low quality raw materials.

The actual appearance of Ötzi the Iceman

Hikers discovered Ötzi’s mummified body in a gully high in the Italian Alps in 1991. His frozen remains are perhaps the most intensely studied archaeological find in the world, revealing in unprecedented detail what life was like 5,300 years ago. shin.

His stomach has information about his last meal and where he came from, his arms revealed he was right-handed, and his clothes gave a rare insight into what ancient people wore.

But a new analysis of DNA extracted from Ötzi’s pelvis in August revealed that his physical appearance was not what scientists first thought.

The study of his genetic makeup showed that Ötzi the Iceman had dark skin and dark eyes – and was probably bald. This revised appearance is in stark contrast to the famous Ötzi reconstruction which shows a thin-skinned man with a full head of hair and beard.

The wearer revealed a 20,000 year old crocodile

Archaeologists often find bone tools and other artefacts from ancient sites, but it is impossible to know for sure who used or wore them.

Earlier this year, scientists recovered ancient human DNA from a deer bone shark found in Denisova Cave in Siberia. With that clue, they were able to reveal that the person who lived was a woman who lived between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago.

She belonged to a group known as the Old North Indians, who are genetically related to the first Americans.

Human DNA is likely preserved in the deer bone rug because it is porous and therefore more likely to retain genetic material present in skin cells, sweat and other body fluids.

It is not known why the deer tooth skull contained so much DNA of the ancient woman (about the same amount as a human tooth). It may have been very loved and worn close to the skin for an extremely long time, said Elena Essel, a molecular biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who developed a new technique to extract the DNA.

The damaged ancient scroll decoded by AI

Around 1,100 scrolls were burnt to a crisp during the famous eruption of Vesuvius nearly 2,000 years ago. In the 1700s, some enterprising excavators found the huge treasure in volcanic mud.

The collection, known as the Herculaneum scrolls, may be the largest known library from classical antiquity, but the contents of the fragile documents remained a mystery until a University of Nebraska computer science student won a science competition. earlier this year.

With the help of artificial intelligence and computed tomography imaging, Luke Farritor was the first person to decode a word written in Ancient Greek on one of those black scrolls.

Farritor was awarded $40,000 for coining the word “πορφυρας” or “porphyras”, which is the Greek word for purple. Researchers are hopeful that it won’t be long until complete scrolls can be found using the technique.

The materials needed to make a mummy

From fragments of discarded pots in an embalming workshop, scientists have discovered some of the substances and concoctions used by the ancient Egyptians to mummify the dead.

By chemically analyzing organic residues left in the vessels, the researchers determined that the ancient Egyptians used a wide range of substances to anoint the body after death, to reduce unpleasant odors and to protect it from fungus, bacteria and putrefaction. Among the materials identified are plant oils such as juniper, cypress and beeswax, as well as resins from pistachio trees, animal fat and beeswax.

Although scholars had previously learned the names of substances used to embalm the dead from Egyptian texts, they had – until recently – only been able to guess exactly what the compounds and materials were. which they referred to.

The ingredients used in the workshop were diverse and came not only from Egypt, but much further afield, suggesting that goods were exchanged over long distances.

Beethoven: A family secret revealed – but one mystery lives on

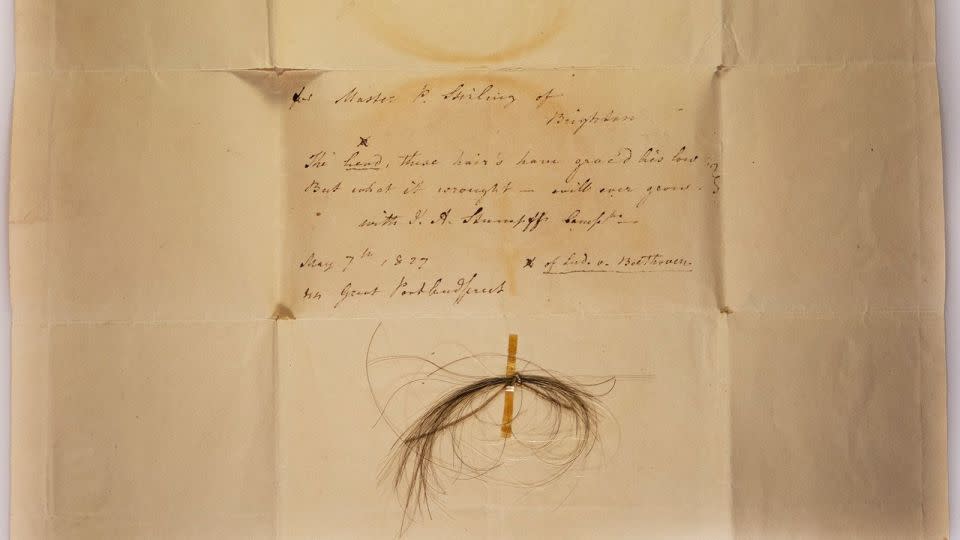

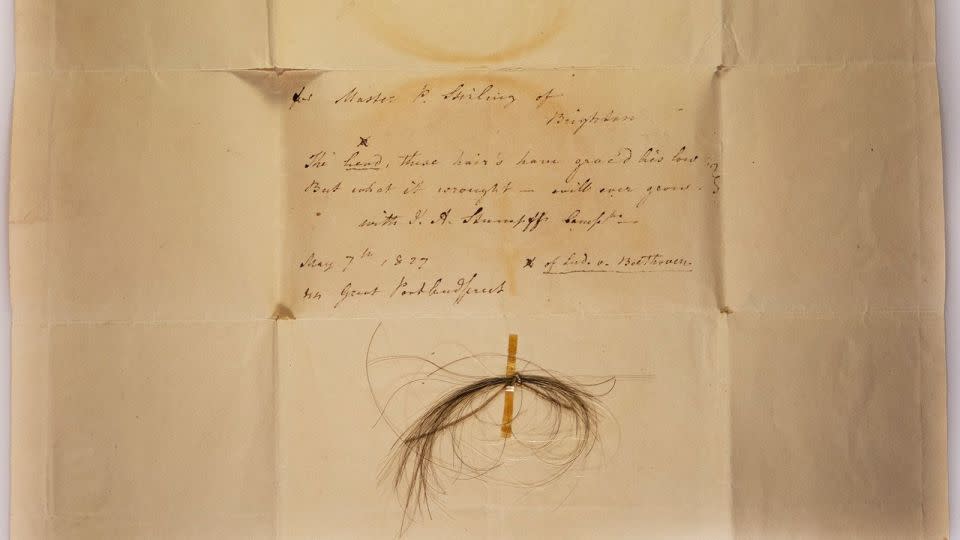

Composer Ludwig van Beethoven died aged 56 in 1827 after a series of chronic health problems, including hearing loss, gastrointestinal issues and liver disease.

Beethoven wrote a letter to his brothers in 1802 asking his doctor, Johann Adam Schmidt, to investigate the nature of the composer’s illness when he died. The letter is called the Heiligenstadt Testament.

Almost 200 years after his death, scientists extracted DNA from preserved locks of hair in an attempt to honor this request.

The team was unable to reach a definitive diagnosis, but Beethoven’s genetic data helped the researchers rule out possible causes such as the autoimmune disease celiac disease, lactose intolerance or irritable bowel syndrome.

The genetic information also indicated that an extramarital affair had occurred in the composer’s family.

Ashley Strickland and Taylor Nicioli contributed to this report.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com